Two billion people don’t have safe drinking water: what does this really mean for them?

For billions, it can mean hours spent collecting water. For almost a million, it means dying from disease.

In the time it would take me to write the next sentence, I could get up, walk to the kitchen, and pour myself a glass of clean water. I’ve never had to worry about whether that water would make me sick.

Almost six billion other people in the world share this reality. They have safe drinking water in their homes, ready whenever needed.

That still leaves two billion people without. That’s the most important number in this article: two billion people who don’t have safe water to drink.

But these large numbers can seem abstract. It’s not clear what this means in practice. If people don’t have safe water, what are they drinking? What does it mean for their daily lives?

Here, I want to answer these questions and bring a more human perspective that sometimes gets lost when we’re talking about millions or billions of people.

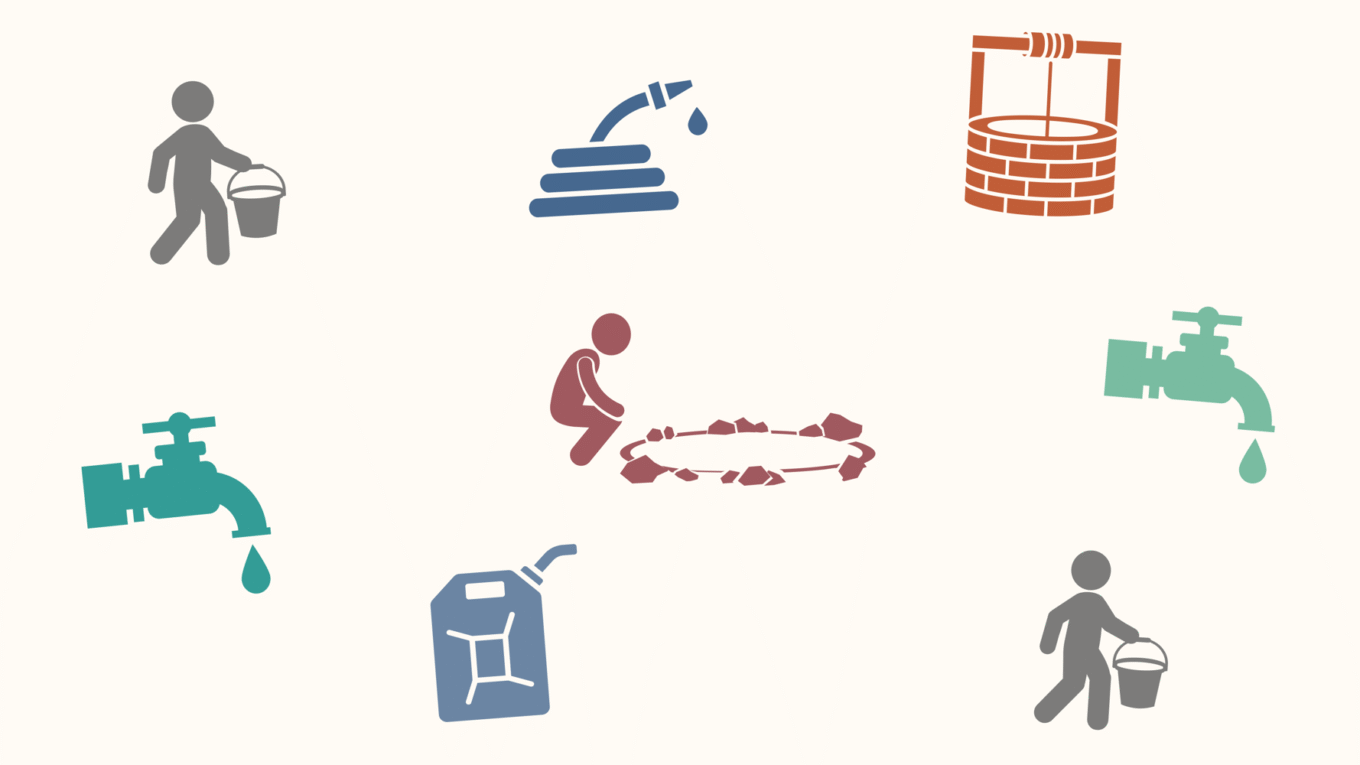

Before we get into some of the personal stories and accounts, it’s important to understand how levels of drinking water services are defined and how many people fall on each “rung” of the ladder. I’ve summarized this in the diagram below based on data from the WHO and UNICEF.1

For someone to have “safe drinking water”, their water source needs to meet three criteria: it needs to be free from contamination, located at home, and available whenever needed. Again, this is the reality for almost six billion people.

What are the other two billion drinking? If you’d asked me in the past, I might have guessed that most people without safe drinking water were collecting water from streams or lakes. The world was binary: you either had safe piped water or were collecting it from a river. But that’s not the reality: people collecting surface water are in the minority. Only around 156 million people get their water this way. That’s 1.4% of the global population.

The vast majority of the two billion — around three-quarters of them — do have access to a piped water source or protected well that is probably safe to drink. But it’s either not located in their home, is not always available, or there’s no guarantee it’s completely contamination-free. That usually means they must travel to get there; whether that round-trip takes less or more than 30 minutes determines whether they fall into the “basic source” or “limited source” category. This is summarized in the diagram below.

We’ll now look at the realities for families in each of the categories above. To do this, I’ve relied heavily on the Dollar Street project, built by Anna Rosling Rönnlund at Gapminder.2 It lets us see the realities of daily life for more than 250 families across 50 countries — from the very poorest to some of the richest.

Although families on different rungs of the “drinking water ladder” can have very different experiences, the costs of not having safe drinking water are the same. There are two main ones (which I’ll expand on later).

The first is the most obvious. Drinking contaminated water can spread disease, make us sick, and in many cases, can be fatal.

The second thing we think about less is the time it takes to collect this water. For many families, it can be tens of hours every week. That’s extremely far from my reality, where walking to the kitchen tap takes seconds.

That’s 7% of people without safe drinking water

Meet J and D, and their six children. The couple lives in Burundi, and they earn around $41 per month each, which means they live in extreme poverty.3

They farm on their own land, which provides most of their food. They built their three-bedroom house themselves.

They do not have safe drinking water. Instead, D and her children spend 14 hours a week — two hours a day — fetching water from a small stream nearby.

In the video, you can see them using a small plastic jerry can to collect the water from the river. In the next photo, one of the children is drinking from it.

There’s no guarantee that the stream water is safe to drink. It could contain chemicals, fertilizers, or pesticides washing off from farms upstream; bacteria from animal waste; or viruses and parasites from biological sources. Everyone in the family is at risk of developing diarrheal or bacterial diseases, which can be particularly damaging for people living in poverty because they are often already malnourished or have limited access to healthcare and medicines.

The time spent collecting the water is also a problem. Those 14 hours a week could be spent on work to increase the family’s income. For the children, it could mean the opportunity to go to school, read, play, or improve their skills in other areas. D and her kids spend another 21 hours a week collecting firewood. That’s almost a full-time job spent collecting water and wood.

Another 156 million people are in the same situation as J and D. That’s still a lot, equal in size to the population of Russia. But it’s important to note that this is not the reality for most people who don’t have access to safe drinking water. Even in low-income countries, just 5% of people get their water from streams, rivers, or ponds.

That’s 14% of people without safe drinking water

On the next run of the water ladder, you’ll find B. She lives with her husband and four children in Burkina Faso. In the photograph, you can see her cycling to collect water for the family.

Both adults in the family earn the equivalent of around $53 per month, which again, means they live in extreme poverty.

The nearest well is a two-hour walk away. Since D cycles, the journey is a bit faster, but she still spends 40 hours every week collecting water and firewood.4 With six family members to provide for and limited space to carry water on the back, she probably has to make several daily trips.

The video shows her filling water cans with a hose. This hose is connected to an unprotected well, which means the water is unsafe to drink.

While D’s situation differs from that of the previous family because she isn’t fetching water from streams or lakes, the problems are similar: collecting water is almost a full-time job, and the family is at risk of getting sick.

Some families don’t have to travel quite as far: this family in Kenya does not have access to a clean water source, but the water they collect is “only” 30 minutes — rather than 2 hours — away.

D is among the almost 300 million people (a population the size of Indonesia) with an “unimproved” water source.5 It’s from a well or a spring, but that water source is not protected from pollution.

Combined with those who rely on surface water, around 5% of the world’s population relies on water from an “unimproved” source. The other 95% have a piped system, protected spring, well, borehole, or safe bottled water. While it’s not guaranteed, most will have clean water that is much less likely to make them ill. We’ll look at their realities now.

That’s 13% of people without safe drinking water

Many people in this category probably do have safe drinking water — at least at its initial source point — but it’s either hard to verify as contamination-free, or it’s far from home and takes a long time to collect.

T and her husband live with their five children and sister in Haiti.

The house has no running water, but safe water can be collected from public piped systems. You can see T filling buckets in the photograph. The problem is that the family spends 70 hours a week fetching it, the equivalent of two full-time jobs.

They might be free from the worry of disease and infection, but it’s a huge time investment with a clear opportunity cost for other forms of work, education, and free time.

This is a common experience. This mother and her daughters in the Philippines spend 7 hours a week collecting safe water, a 60-minute trip every time.

That’s 66% of people without safe drinking water

1.5 billion people are in the same situation as those families above, but collecting water doesn’t take them as long. These are families with access to an improved water source — which means it’s probably safe to drink, but not guaranteed — but it’s not in their own home or available all the time.

This family in India has safe drinking water, but it takes around 20 minutes to collect. As shown in the video, someone — often one of the women — uses a public water pump to retrieve it.

Across the Indian Ocean in Sub-Saharan Africa, this family from Ghana — shown in the photograph — does the same using a public source around 10 minutes from home.

That saves a lot more time compared to the families that spend tens of hours every week fetching water. But it’s still a relatively foreign concept for people living in conditions where water is available at home, whenever they need it.

That brings us to the final group: most people worldwide have safe water to drink at home (inside or on the premises).

Most people in high-income countries live this reality, but many people in middle and low-income countries experience this, too.

This family in Togo — who spend most of their income on food and still rely on wood for cooking — has a safe water supply at home. In the video, you can see them pouring water from the tap.

While income is a good predictor of who will and won’t have safe drinking water, location and circumstances matter too. A family could have a moderate income, but if they’re in an extremely remote area without piped networks and accessible wells, it’s difficult to get clean water easily. The opposite is also true: some low-income families could find themselves close to safe water sources that are easy to tap into.

Our next family is a clear example: in the photograph, you can see J, R, and their 8 children. They live in the Philippines. Each adult earns around $94 per month, which, shared among the family, means they live in extreme poverty.

But they do have a clean water source in their yard. Even though it’s not in the house, they would still meet the criteria for having safe drinking water. Of course, this category — the top rung of the drinking water ladder — extends to much richer families. This family in South Africa not only has safe water from the tap in their house, but also a fancy refrigerator to keep it cool.

Other parts of daily life for the families from Togo, the Philippines, and South Africa are very different. However, when it comes to drinking water, their experiences are similar. It doesn’t take them long to pour it, and they can drink it with the confidence that neither they nor their children will get sick. That’s ultimately what people want and need.

“Safe drinking water” only became the main indicator of progress on clean water in 2017. Before that, the focus was on the number of people who had access to an “improved water source.”

An improved water source can potentially deliver safe water: it’s a protected pipe, spring, borehole, or other system that probably delivers safe water.

The problem is that it doesn’t guarantee the water is safe at the point of consumption. Imagine you collect a bucket of water from a pipe an hour from home. It might be safe when you collect it, but once you’ve trekked an hour back and left it sitting unrefrigerated in the heat for the rest of the day, there’s no guarantee that it’s free of pathogens when you drink it the next morning.

That’s the key point here. 95% of the world uses an improved water supply. As the map below shows, the majority in every country does, even in the poorest countries.6

Many countries have rapidly increased this share in the last few decades. In the slope chart, you can see the change in the share of the population with improved water for a selection of countries that still had pretty poor coverage in 2000. In Ethiopia, for example, access has tripled from just 26% to 80%.

Countries can quickly increase access to a (probably) clean piped, spring, or borehole source. The biggest challenge is getting those pipes into each individual household and making sure that the source is completely contamination-free. This aspect is harder, and often means expanding a single community-shared pipe into a whole water network. This is even more difficult in rural settings where infrastructure is less concentrated.

But to get universal access to safe drinking water, this is what the world will need to do.

Researching this article has helped me understand these abstract definitions and numbers. I hope they’ve clarified some of this for you, too.

I want to close by highlighting, again, the costs of not having safe drinking water.

The one I had underappreciated was the amount of time that some families spend collecting water. This is often women or children. We saw that this could take 70 hours a week in the most extreme examples. For most of us, that seems unfathomable: imagine that collecting water was a full-time job for not only you but another member of your family.

The second is more obvious, but still a huge global problem. Unsafe water leads to more than 800,000 deaths every year.7 This is because it can lead to the spread of diarrheal diseases, such as cholera or dysentery, and other diseases, including polio and hepatitis. It can also lead to malnutrition, which is attributed to half of all childhood deaths.8

These deaths tend to be concentrated in lower-income countries where fewer people have safe water to drink. As you can see on the map, in some of the worst-off countries, more than 5% of all deaths are attributed to unsafe water.

Again, a number as large as 800,000 can seem abstract. But that’s 800,000 families that have to endure the loss of a loved one, often their own child. What’s perhaps even more painful is that they died from one of the few things that humans need to stay alive.

Very few people in the world know this better than Haja, a young mother from Sierra Leone. She lost three children in just three years; two of them were small babies when they died from diarrheal diseases as a result of unsafe water.

As she puts it, “I have given birth to six children, but I only have three alive.”

That’s the reality of not having safe water to drink. Every day, you have no choice but to give your children, siblings, parents, or grandparents the very thing that could kill them.

Acknowledgments

I relied heavily on Dollar Street — a project published by Gapminder and Anna Rosling Rönnlund — for the stories and visuals used in this article. Many thanks to them for this work and for making it available for reuse. I highly recommend it if you want to explore more of these experiences and living conditions across the world.

I would also like to thank Ike Saunders, Daniel Bachler, Esteban Ortiz-Ospina, Edouard Mathieu, Joe Hasell, Fiona Spooner, Saloni Dattani, and Simon van Teutem for comments and feedback on this work.

Cite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this article, please also cite the underlying data sources. This article can be cited as:

Hannah Ritchie (2025) - “Two billion people don’t have safe drinking water: what does this really mean for them?” Published online at OurWorldinData.org. Retrieved from: 'https://ourworldindata.org/what-no-safe-water-means' [Online Resource]BibTeX citation

@article{owid-what-no-safe-water-means,

author = {Hannah Ritchie},

title = {Two billion people don’t have safe drinking water: what does this really mean for them?},

journal = {Our World in Data},

year = {2025},

note = {https://ourworldindata.org/what-no-safe-water-means}

}Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.