I Replaced Animal Crossing’s Dialogue with a Live LLM by Hacking GameCube Memory

A bridge from 2001 to today, with no game code changes required.

.png)

Animal Crossing. Infamous for its charming but ultimately repetitive dialogue. Having picked up the GameCube classic again, I was shocked (/s) to discover that the villagers still say the same things they did 23 years ago. Let’s change that.

The problem? The game runs on a Nintendo GameCube, a 24-year-old console with a 485 MHz PowerPC processor, 24MB of RAM, and absolutely no internet connectivity. It was fundamentally, physically, and philosophically designed to be an offline island.

This is the story of how I built a bridge from 2001 to today, making a vintage game console talk to a cloud-based AI without modifying a single line of the original game’s code.

The First Hurdle: Speaking to the Game 🗣️

My first stroke of luck was immense. The week I started this project, a massive effort by the Animal Crossing decompilation community reached completion. Instead of staring at PowerPC assembly, I had access to readable C code.

Digging through the source, I quickly found the relevant functions under a file named m_message.c. This was it, the heart of the dialogue system. A simple test confirmed I could hijack the function call and replace the in-game text with my own string.

C: A glimpse into the decompiled dialogue system

// A glimpse into the decompiled Animal Crossing source code

// The function that changes message data in the dialogue system.

// My initial entry point for hijacking the text.

extern int mMsg_ChangeMsgData(mMsg_Window_c* msg_p, int index)

if (index >= 0 && index < MSG_MAX && mMsg_LoadMsgData(msg_p->msg_data, index, FALSE))

msg_p->end_text_cursor_idx = 0;

mMsg_Clear_CursolIndex(msg_p);

mMsg_SetTimer(msg_p, 20.0f);

return TRUE;

return FALSE;

Easy win, right? But changing static text is one thing. How could I get data from an external AI into the game in real time?

My first thought was to just add a network call. But that would mean writing an entire network stack for the GameCube from scratch (TCP/IP, sockets, HTTP) and integrating it into a game engine that was never designed for it. That was a non-starter.

My second thought was to use the Dolphin emulator’s features to write to a file on my host machine. The game would write a “request” file with context, and my Python script would see it, call the LLM, and write back a “response” file. Unfortunately, I couldn’t get the sandboxed GameCube environment to access the host filesystem. Another dead end.

The Breakthrough: The Memory Mailbox 📬

The solution came from a classic technique in game modding: Inter-Process Communication (IPC) via shared memory. The idea is to allocate a specific chunk of the GameCube’s RAM to act as a “mailbox.” My external Python script can write data directly into that memory address, and the game can read from it.

graph TD

A[Python Script] — “Writes LLM response” –> BMemory Mailbox @ 0x81298360

B — “Game reads new dialogue” –> C[Animal Crossing on Dolphin Emulator]

C — “Writes current speaker & context” –> B

Python: The core of the “Memory Mailbox” interface

# This is the bridge. These functions read from and write to GameCube RAM via Dolphin.

GAMECUBE_MEMORY_BASE = 0x80000000

def read_from_game(gc_address: int, size: int) -> bytes:

"""Reads a block of memory from a GameCube virtual address."""

real_address = GAMECUBE_MEMORY_BASE + (gc_address - 0x80000000)

return dolphin_process.read(real_address, size)

def write_to_game(gc_address: int, data: bytes) -> bool:

"""Writes a block of data to a GameCube virtual address."""

real_address = GAMECUBE_MEMORY_BASE + (gc_address - 0x80000000)

return dolphin_process.write(real_address, data)

This was the path forward. But it created a new, painstaking task: I had to become a memory archaeologist. I needed to find the exact stable memory addresses for the active dialogue text and the current speaker’s name.

To do this, I wrote my own memory scanner in Python. The process was a tedious loop:

- Talk to a villager. The moment their dialogue box appeared, I’d freeze the emulator.

- Scan. I’d run my script to scan all 24 million bytes of the GameCube’s RAM for the string of text on screen (e.g., “Hey, how’s it going?”).

- Cross-Reference. This often returned multiple addresses. So, I’d unfreeze, talk to a different villager, and scan for their name to figure out which memory block belonged to the active speaker.

After hours of talking, freezing, and scanning, I finally nailed down the key addresses: 0x8129A3EA for the speaker’s name and 0x81298360 for the dialogue buffer. I could now reliably read who was talking and, more importantly, write data back to the dialogue box.

What About the GameCube Broadband Adapter? 🌐

Yes, the GameCube had an official Broadband Adapter (BBA). But Animal Crossing shipped without networking primitives, sockets, or any game-layer protocol to use it. Using the BBA here would have required building a tiny networking stack and patching the game to call it. That means: hooking engine callsites, scheduling async I/O, and handling retries/timeouts, all inside a codebase that never expected the network to exist.

- Engine hooks: Hijack safe points in the message loop to send/receive packets.

- Driver/protocol: Provide a minimal UDP/RPC interface over BBA.

- Robustness: Handle timeouts, retries, and partial reads without stalling animations/UI.

graph LR

subgraph Option A: BBA Network Shim

AC[Animal Crossing] –> Hooks[Net Shim Hooks]

Hooks –> BBA[BBA Driver]

BBA –> LAN[(LAN)]

LAN –> Host[Host Bridge Server]

end

subgraph Option B: RAM Mailbox

AC2[Animal Crossing] –> Mailbox[RAM Mailbox]

Mailbox –> Py[Python Watcher]

Py –> LLM[LLM]

end

I chose the RAM mailbox because it’s deterministic, requires zero kernel/driver work, and stays entirely within the emulator boundary, with no binary network stack needed. That said, a BBA shim is absolutely possible (and a fun future project for real hardware via Swiss + homebrew).

C: Minimal RPC envelope for a hypothetical BBA shim

#include <stdint.h>

/* Minimal RPC envelope for a hypothetical BBA shim */

typedef struct

uint32_t magic; // 'ACRP'

uint16_t type; // 1=Request, 2=Response

uint16_t length; // payload length

uint8_t payload[512];

RpcMsg;

int ac_net_send(const RpcMsg* msg); // sends via BBA

int ac_net_recv(RpcMsg* out, int timeoutMs); // polls with timeout

Python: Host-side UDP bridge (very simplified)

import socket, json

sock = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_DGRAM)

sock.bind(("0.0.0.0", 19135))

while True:

data, addr = sock.recvfrom(2048)

msg = json.loads(data.decode("utf-8", "ignore"))

# ... call Writer/Director LLMs ...

reply = json.dumps("ok": True, "text": "Hi from the cloud!").encode()

sock.sendto(reply, addr)

Speaking the Game’s Secret Language 🤫

I eagerly tried writing “Hello World” to the dialogue address and… the game froze. The character animations kept playing, but the dialogue wouldn’t advance. I was so close, yet so far.

The problem was that I was sending plain text. Animal Crossing doesn’t speak plain text. It speaks its own encoded language filled with control codes.

Think of it like HTML. Your browser doesn’t just display words; it interprets tags like <b> to make text bold. Animal Crossing does the same. A special prefix byte, CHAR_CONTROL_CODE, tells the game engine, “The next byte isn’t a character, it’s a command!”

These commands control everything: text color, pauses, sound effects, character emotions, and even the end of a conversation. If you don’t send the <End Conversation> control code, the game simply waits forever for a command that never comes. That’s why it was freezing.

Once again, the decompilation community saved me. They had already documented most of these codes. I just needed to build the tools to use them.

I wrote an encoder and a decoder in Python. The decoder could read raw game memory and translate it into a human-readable format, and the encoder could take my text with custom tags and convert it back into the exact sequence of bytes the GameCube understood.

Python: A small sample of the control codes I had to encode/decode

# A small sample of the control codes I had to encode/decode

CONTROL_CODES =

0x00: "<End Conversation>",

0x03: "<Pause [:02X]>", # e.g., <Pause [0A]> for a short pause

0x05: "<Color Line [:06X]>", # e.g., <Color Line [FF0000]> for red

0x09: "<NPC Expression [Cat::02X] []>", # Trigger an emotion

0x59: "<Play Sound Effect []>", # e.g., <Play Sound Effect [Happy]>

0x1A: "<Player Name>",

0x1C: "<Catchphrase>",

# The magic byte that signals a command is coming

PREFIX_BYTE = 0x7F

With my new encoder, I tried again. This time, I wasn’t just sending text. I was speaking the game’s language. And it worked. The hardest part of the hack was done.

Building the AI Brain 🧠

With the communication channel established, it was time for the fun part: building the AI.

My initial approach was to have a single LLM do everything: write dialogue, stay in character, and insert the technical control codes. The results were a mess. The AI was trying to be a creative writer and a technical programmer simultaneously and was bad at both.

The solution was to split the task into a two-model pipeline: a Writer and a Director.

- The Writer AI: This model’s only job is to be creative. It receives a detailed character sheet (which I generated by scraping the Animal Crossing Fan Wiki) and focuses on writing dialogue that is funny, in-character, and relevant to the context.

- The Director AI: This model receives the pure text from the Writer. Its job is purely technical. It reads the dialogue and decides how to “shoot the scene.” It adds pauses for dramatic effect, emphasizes words with color, and chooses the perfect facial expression or sound effect to match the mood.

This separation of concerns worked perfectly.

graph LR

subgraph Game World

Dolphin(Dolphin Emulator)

end

subgraph Python Bridge

Watcher(watch_dialogue.py)

Encoder(Encoder/Decoder)

end

subgraph AI Core

Writer(Writer LLM)

Director(Director LLM)

end

subgraph External Data

Wiki(Fan Wiki)

News(RSS Feeds)

end

Dolphin <–> |IPC via RAM| Watcher

Watcher –> |Context| Writer

Wiki –> |Character Sheets| Writer

News –> |Current Events| Writer

Writer –> |Raw Dialogue| Director

Director –> |Decorated Dialogue| Encoder

Encoder –> |Encoded Bytes| Watcher

Emergent Behavior 🤪

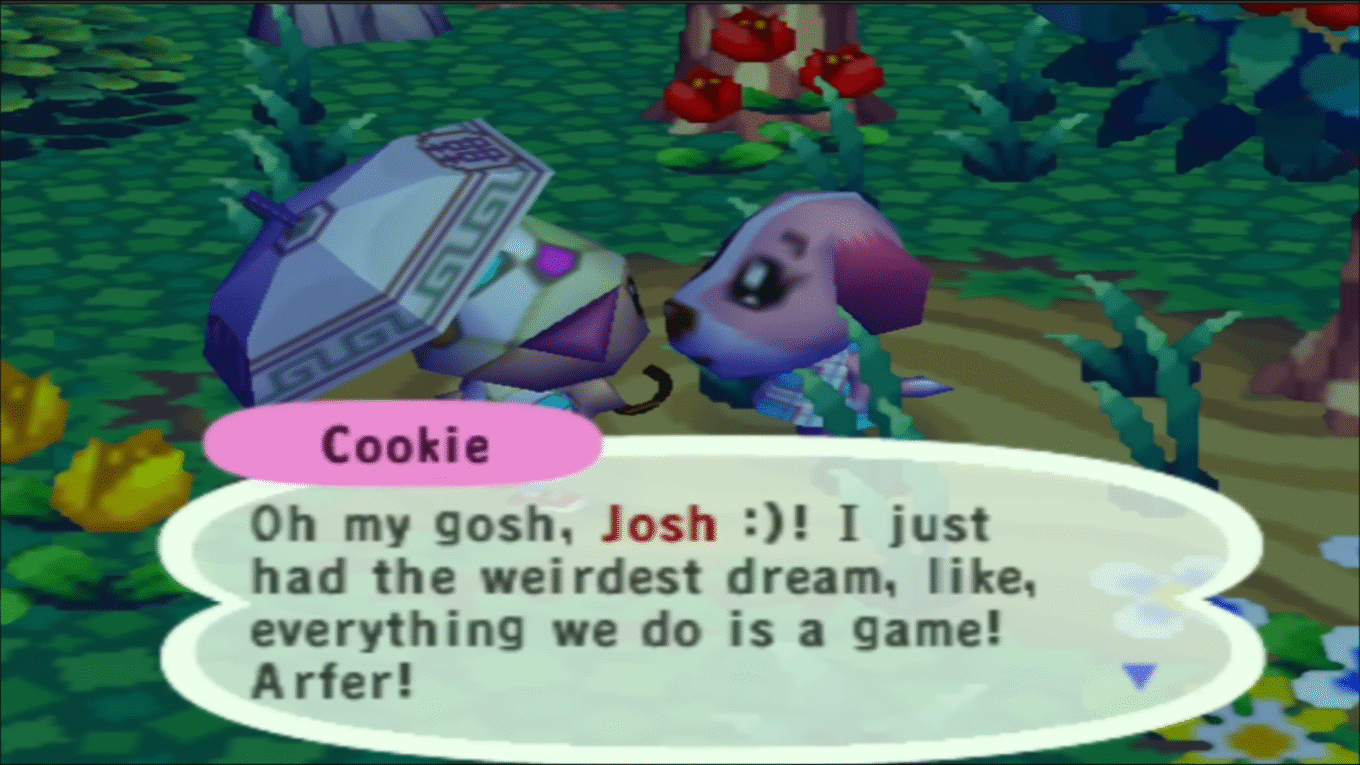

First I piped in a lightweight news feed. Within minutes, villagers began weaving headlines into small talk, no prompts, just context.

.png)

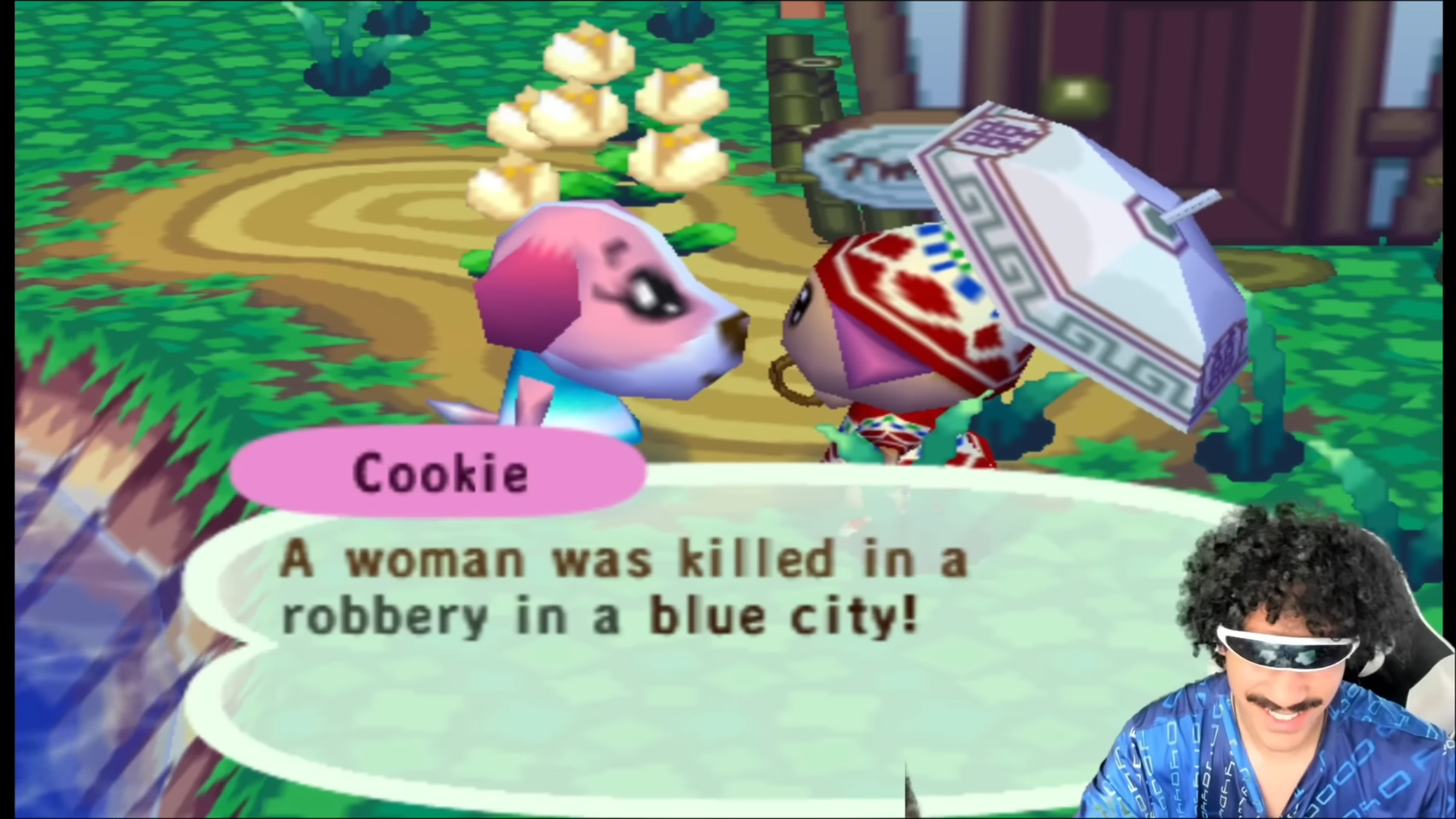

Then I gave them a tiny shared memory for gossip, who said what, to whom, and how they felt. Predictably, it escalated into an anti-Tom Nook movement.

.png)

And I was reminded that I used Fox News as the news feed.

Now the game is a strange, hilarious, and slightly unsettling 🙂

All the code for this project, including the memory interface, dialogue encoder, and AI prompting logic, is available on GitHub. It was one of the most challenging and rewarding projects I’ve ever tackled, blending reverse engineering, AI, and a deep love for a classic game.

Watch the full video: Modern AI in a 24-Year-Old Game