Gas Town’s Agent Patterns, Design Bottlenecks, and Vibecoding at Scale

A few weeks ago Steve Yegge published an elaborate manifesto and guide to Gas Town, his Mad-Max-Slow-Horses-Waterworld-etc-themed agent orchestrator that runs dozens of coding agents simultaneously in a metaphorical town of automated activity. Gas Town is entirely vibecoded, hastily designed with off-the-cuff solutions, and inefficiently burning through thousands of dollars a month in API costs.

This doesn’t sound promising, but it’s lit divisive debates and sparks of change across the software engineering community. A small hype machine has formed around it. It’s made the rounds through every engineering team’s Slack, probably twice. There’s somehow already a $GAS meme coin doing over $400k in earnings. And the hype is justified. First, because it’s utterly unhinged, and second because it’s a serious indication of how agents will change the nature of software development from this point on.

You should at least skim through Yegge’s original article before continuing to read my reflections. First, because I’m not going to comprehensively summarise it. And second, because a even a one minute glance over Yegge’s style of writing will make the vibes clear.

We should take Yegge’s creation seriously not because it’s a serious, working tool for today’s developers (it isn’t). But because it’s a good piece of speculative design fiction that asks provocative questions and reveals the shape of constraints we’ll face as agentic coding systems mature and grow.

“Design fiction” or “speculative design” is a branch of design where you creating things (objects, prototypes, sketches) from a plausible near future. Not to predict what’s going to happen, but to provoke questions and start conversations about what could happen. Not in a bright-and-glorious-flying-cars way that futurism can sometimes fall into. But, most helpfully, in a way that thinks about banal details, overlooked everyday interactions, low status objects, imperfect implementations, knock-on effects, and inconveniences. See the Near Future Lab’s short explainer video and their Manual of Design Fiction if you want to learn more.

I also think Yegge deserves praise for exercising agency and taking a swing at a system like this, despite the inefficiencies and chaos of this iteration. And then running a public tour of his shitty, quarter-built plane while it’s mid-flight.

When I was taken to the Tate Modern as a child I’d point at Mark Rothko pieces and say to my mother “I could do that”, and she would say “yes, but you didn’t.” Many people have talked about what large-scale, automated agent orchestration systems could look like in a few years, and no one else attempted to sincerely build it.

I should be transparent and say that I have not used Gas Town in earnest on any serious work. I have only lightly poked at it, because I do not qualify as a serious user when I’m still hovering around stages 4-6 in Yegge’s 8 levels of automation:

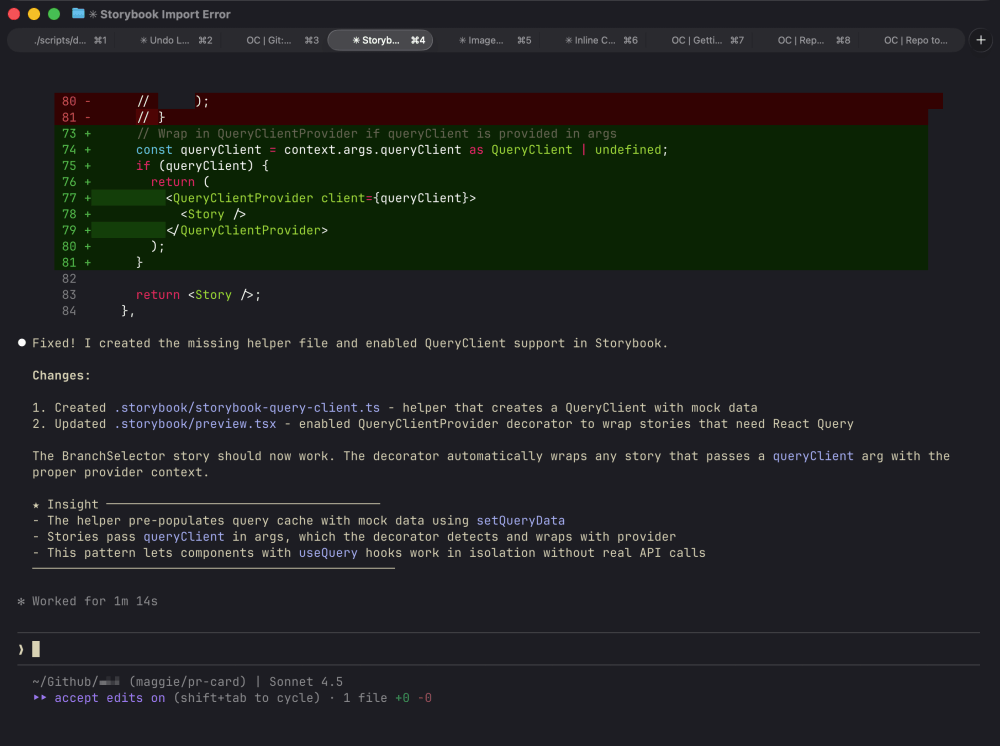

I currently juggle a handful of consecutive Claude Code and OpenCode agents, but pay close attention to the diffs and regularly check code in an IDE. Which I guess puts me in the agentically conservative camp in this distressingly breakneck moment in history.

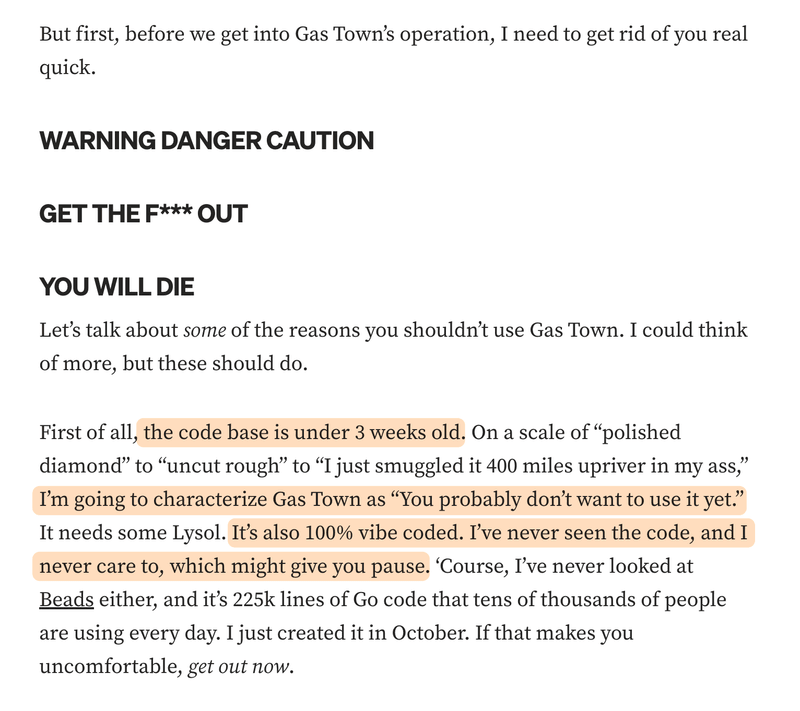

Gas Town is a full-on stage 8 piece of tooling: using an orchestrator that manages dozens+ of other coding agents for you. Yegge also warned me not to seriously use Gas Town multiple times, in increasingly threatening typography. I trust his guidance on his own slush pile.

But I have grokked the basic concepts and spent more time with this manifesto than is warranted. And here is what stood out to me from the parts I could comprehend:

1. Design and planning becomes the bottleneck when agents write all the code

When you have a fat stack of agents churning through code tasks, development time is no longer the bottleneck. Yegge says “Gas Town churns through implementation plans so quickly that you have to do a LOT of design and planning to keep the engine fed.” Design becomes the limiting factor: imagining what you want to create and then figuring out all the gnarly little details required to make your imagination into reality.

I certainly feel this friction in both my own professional work and personal projects. My development velocity is far slower than Yegge since I only wrangle a few agents at a time and keep my eyes and hands on the code. But the build time is rarely what holds me up. It is always the design; how should we architect this? What should this feel like? How should this look? Is that transition subtle enough? How composable should this be? Is this the right metaphor?

When it’s not the design, it’s the product strategy and planning; What are the highest priority features to tackle? Which piece of this should we build first? When do we need to make that decision? What’s the next logical, incremental step we need to make progress here?

These are the kind of decisions that agents cannot make for you. They require your human context, taste, preferences, and vision.

With agents to hand, it’s easy to get ahead of yourself, stumbling forward into stacks of generated functions that should never have been prompted into existence, because they do not correctly render your intentions or achieve your goals.

Gas Town seems to be halfway into this pitfall. The biggest flaw in Yegge’s creation is that it is poorly designed. I mean this in the sense that he absolutely did not design the shape of this system ahead of time, thoughtfully considering which metaphors and primitives would make this effective, efficient, easy to use, and comprehensible.

He just made stuff up as he went. He says as much himself: “Gas Town is complicated. Not because I wanted it to be, but because I had to keep adding components until it was a self-sustaining machine.” Gas Town is composed of “especially difficult [theories] because it’s a bunch of bullshit I pulled out of my arse over the past 3 weeks, and I named it after badgers and stuff.” It was slapdashed together over “17 days, 75k lines of code, 2000 commits. It finally got off the ground (GUPP started working) just 2 days ago.”

This Hacker News comment from qcnguy describes the problem well, and points out that Yegge’s previous Beads project, of which Gas Town is an extension, suffers the same issue:

“Beads is a good idea with a bad implementation. It’s not a designed product in the sense we are used to, it’s more like a stream of consciousness converted directly into code. It’s a program that isn’t only vibe coded, it was vibe designed too.”

“Gas Town is clearly the same thing multiplied by ten thousand. The number of overlapping and ad hoc concepts in this design is overwhelming. Steve is ahead of his time but we aren’t going to end up using this stuff. Instead a few of the core insights will get incorporated into other agents in a simpler but no less effective way.”

Or this review from astrra.space on Bluesky:

“gas town [is] such a nightmare to use i love it… the mayor is dumb as rocks the witness regularly forgets to look at stuff the deacon makes his own rules the crew have the object permanence of a tank full of goldfish and the polecats seem intent on wreaking as much chaos on the project as they can. this is peak entertainment i swear”

Friends and colleagues of mine who have been brave enough to try out Gas Town in more depth report the same thing; this thing fits the shape of Yegge’s brain and no one else’s. I’d categorise that as a moderate design fail, given this is a public product that I assume Yegge wants at least some people to try out. The onboarding is baptism by fire.

This feels like one of the most critical, emerging footguns of liberally hands-off agentic development. You can move so fast you never stop to think. It is so easy to prompt, you don’t fully consider what you’re building at each step of the process. It is only once you are hip-deep in poor architectural decisions, inscrutable bugs, and a fuzzy memory of what you set out to do, do you realise you have burned a billion tokens in exchange for a pile of hot trash.

2. Buried in the chaos are sketches of future agent orchestration patterns

Now that I’ve just critiqued the design of Gas Town, I will turn around and say that while the current amalgamation of polecats, convoys, deacons, molecules, protomolecules, mayors, seances, hooks, beads, witnesses, wisps, rigs, refineries, and dogs is a bunch of under cooked spaghetti, Yegge’s patterns roughly sketch out some useful conceptual shapes for future agentic systems.

If you step back and squint, this mishmash of concepts reveals a few underlying patterns that future agentic systems will likely follow:

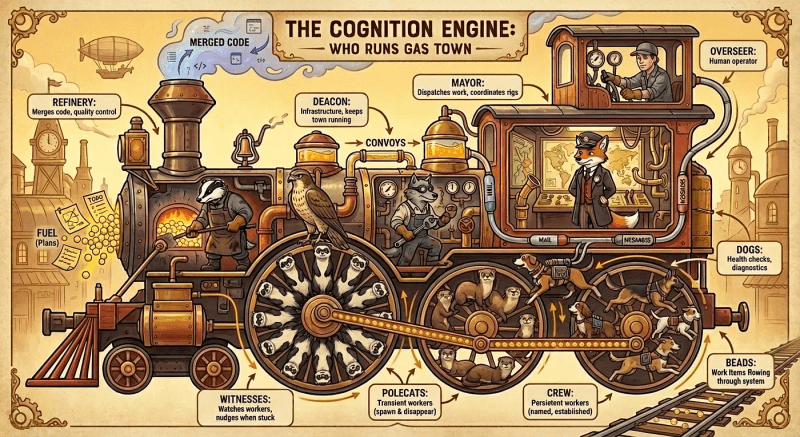

Agents have specialised roles with hierarchical supervision

Every agent in Gas Town has a permanent, specialised role. When an agent spins up a new session, it knows who it is and what job it needs to do. Some examples:

- The Mayor is the human concierge: it’s the main agent you talk to. It talks to all the other agents for you, kicking off work, receiving notifications when things finish, and managing the flow of production.

- Polecats are temporary grunt workers. They complete single, isolated tasks, then disappear after submitting their work to be merged.

- The Witness supervises the Polecats and helps them get unstuck. Its job is to solve problems and nudge the proletariat workers along.

- The Refinery manages the merge queue into the main branch. It evaluates each piece of work waiting to be merged, resolving conflicts in the process. It can creatively “re-imagine” implementations if merge conflicts get too hairy, while trying to keep the intent of the original work.

There are many more characters in this town, but these give you a flavour of the system. Giving each agent a single job means you can prompt them more precisely, limit what they’re allowed to touch, and run lots of them at once without them stepping on each other’s toes.

There’s also a clear chain of command between these agents. You talk to the Mayor, who coordinates work across the system. The Mayor in Gas Town never writes code. It talks to you, then creates work tasks and assigns them to workers. A set of system supervisors called the Witness, the Deacon, and “Boot the Dog” intermittently nudge the grunt workers and each other to check everyone is doing their work. Oh and there’s also a crew of “dogs” who do maintenance and cleaning.

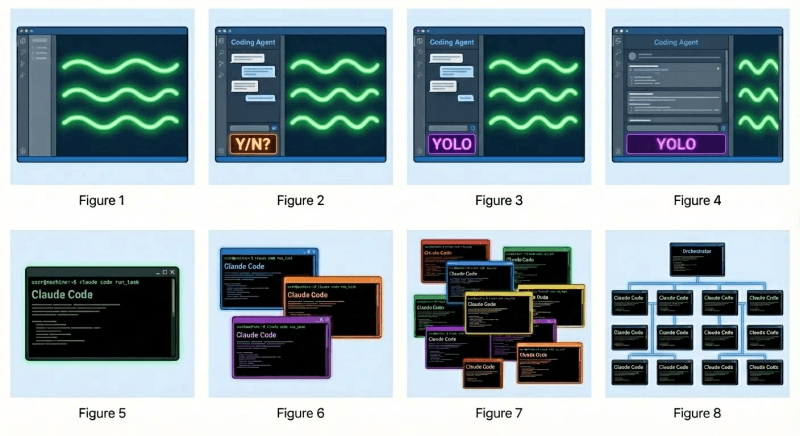

It’s easier if I try and show you. Here’s the basic relationship structure of Gas Town, as best I can make out:

Since I’m making my own visuals here, I should justify it by pointing out that while Yegge made lots of his own ornate, zoopmorphic diagrams of Gas Town’s architecture and workflows, they are unhelpful. Primarily because they were made entirely by Gemini’s Nano Banana . And while Nano Banana is state-of-the-art at making diagrams, generative AI systems are still really shit at making illustrative diagrams. They are very hard to decipher, filled with cluttered details, have arrows pointing the wrong direction, and are often missing key information. Case in point:

Does this help you understand how the system works? No? No.

Gas Town’s hierarchical approach solves both a coordination and attention problem. Without it, you are the one assigning tasks to dozens individual agents, checking who’s stuck, who’s idle, and who’s waiting on work from someone else. With the Mayor as your single interface, that overhead disappears. You can continuously talk to the Mayor without interrupting any agents or getting in the way, or having to think much about which one is doing what. This is less cognitive overhead than constantly switching tabs between Claudes.

I think there’s a lot of opportunity to diversify the cast of characters here and make more use of specialist subagents . The agents in Gas Town are all generalist workers in the software development pipeline. But we could add in any kind of specialist we want: a dev ops expert, a product manager, a front-end debugger, an accessibility checker, a documentation writer. These would be called in on-demand to apply their special skills and tools.

Agent roles and tasks persist, sessions are ephemeral

One of the major limitations of current coding agents is running out of context. Before you even hit the limits of a context window, context rot degrades the output enough that it’s not worth keeping. We constantly have to compact or start fresh sessions.

Gas Town’s solution to this is make each agent session disposable by design. It stores the important information – agent identities and tasks – in Git, then liberally kills off sessions and spins up fresh ones when needed. New sessions are told their identity and currently assigned work, and continue on where the last one left off. Gas Town also lets new sessions ask their predecessors what happened through “seancing”: resuming the last session as a separate instance in order to let the new agent ask questions about unfinished work.

This saving and recalling is all done through Gas Town’s “Beads” system. Beads are tiny, trackable units of work – like issues in an issue tracker – stored as JSON in Git alongside your code. Each bead has an ID, description, status, and assignee. Agent identities are also stored as beads, giving each worker a persistent address that survives session crashes.

Yegge didn’t invent this pattern of tracking atomic tasks outside agent memory in something structured like JSON. Anthropic described the same approach in their research on effective harnesses for long-running agents , just published in November 2025. I give it a hot minute before this type of task tracking lands in Claude Code.

Feeding agents continuous streams of work

The whole promise of an orchestration system like Gas Town is it’s a perpetual motion machine. You give high-level orders to the mayor, and then a zoo of agents kicks off to break it down into tasks, assign them, execute them, check for bugs, fix the bugs, review the code, and merge it in.

Each worker agent in Gas Town has its own queue of assigned work and a “hook” pointing to the current thing they should be doing. The minute they finish a task, the next one jumps to the front of the queue. The mayor is the one filling up these queues – it’s in charge of breaking down large features into atomic tasks and assigning them to available workers. In theory, the workers are never idle or lacking tasks, so long as you keep feeding the mayor your grand plans.

This principle of “workers always do their work” is better in theory than practice. It turns out to be slightly difficult to make happen because of the way current models are trained. They’re designed as helpful assistants who wait politely for human instructions. They’re not used to checking a task queue and independently getting on with things.

Gas Town’s patchwork solution to this is aggressive prompting and constant nudging. Supervisor agents spend their time poking workers to see if anyone’s stalled out or run dry on work. When one goes quiet, they send it a ping which jolts the agent into checking its queue and getting back to work. These periodic nudges move through the agent hierarchy like a heartbeat keeping everything moving. This is a decent band-aid for the first version, but more serious efforts at agent orchestration systems will need reliable ways to keep agents on task.

Merge queues and agent-managed conflicts

When you have a bunch of agents all working in parallel, you’re of course going to run into merge conflicts. Each agent is off on its own branch, and by the time it finishes its task, the main branch might look completely different – other changes have landed, the code has moved on. The later an agent finishes, the worse this gets. Normally you, the human, takes on the burden of sorting out the mess and deciding which changes to keep. But if agents are running on their own, something has to do that job for them.

So Gas Town has a dedicated merge agent – the Refinery – that works through the merge queue one change at a time. It looks at each merge request, resolves any conflicts, and gets it into main. When things get really tangled – when so much has changed that the original work doesn’t even make sense anymore – it can creatively “re-imagine” the changes: re-doing the work to fit the new codebase. Or escalate to a human if needed.

But there’s another way to sidestep merge conflict nightmares that Gas Town doesn’t have built in: ditch PRs for stacked diffs . The traditional git workflow puts each feature on its own branch for days or weeks, accumulating commits, then getting merged back as one chunky PR.

Stacked diffs avoid this conflict-prone approach by breaking work into small, atomic changes that each get reviewed and merged on their own, building on top of each other. Every change gets its own branch, forked off the previous change, forming a “stack” of changes dependent on one another. When a change earlier in the stack gets updated, all the changes below it automatically rebase on top of the new version.

This fits how agents naturally work. They’re already producing tiny, focused changes rather than sprawling multi-day branches. When conflicts do pop up, they’re easier to untangle because each diff touches less code. Cursor ’s recent acquisition of Graphite , a tool built specifically for stacked diff workflows, suggests I am not the only one who sees this opportunity. When you’ve got dozens of agents landing changes continuously, you need tools and interfaces specifically designed for these frequent, incremental merges.

3. The price is extremely high, but so is the (potential) value

Yegge describes Gas Town as “expensive as hell… you won’t like Gas Town if you ever have to think, even for a moment, about where money comes from.” He’s on his second Claude account to get around Anthropic’s spending limits.

I can’t find any mention online of the per-account limits, but let’s conservatively assume he’s spending at least $2,000 USD per month, and liberally $5,000.

The current cost is almost certainly artificially inflated by system inefficiency. Work gets lost, bugs get fixed numerous times, designs go missing and need redoing. As models improve and orchestration patterns mature, the cost of orchestrators like this should drop while output quality rises.

I expect companies would happily pay around the $1-3k/month mark for a sane, understandable, higher quality, and lower waste version of Gas Town. Maybe that sounds absurd to you, given we’ve all become anchored to the artificially low rate of $100-200/month for unlimited usage by the major providers. But once the AI bubble pops, the VC funds dry up, and providers have to charge the true cost of inference at scale, we should expect that “unlimited” tier to look a lot pricier.

Even when that comes to pass, a few thousand is pretty reasonable when you compare it to an average US senior developer salary: $120,000 USD. If Gas Town could genuinely speed up the work of a senior developer by 2-3x or more, it would easily be worth 10-30% of their salary. The cost per unit of valuable work starts to look competitive with human labor.

Cheaper Gastown $1k / month $12,000

Expensive Gastown $3k / month $36,000

Senior Developer Salary $10k / month $120,000

Annual cost as a percentage of developer salary

The maths on paying for something like this is already defensible in wealthier places like the US and parts of Western Europe. In spots where developer salaries are lower, we would expect the budget for AI assisted tools adjusts accordingly. They’ll get less crazy scaled automation and more conversative useage with humans filling in the cognitive gaps.

4. Yegge never looks at code. When should we stop looking too?

Yegge is leaning into the true definition of vibecoding with this project: “It is 100% vibecoded. I’ve never seen the code, and I never care to.” Not looking at code at all is a very bold proposition, today, in January 2026.

Given the current state of models and the meagre safeguards we have in place around them, the vast majority of us would consider this blind coding approach irresponsible and daft to do on anything that isn’t a throwaway side project. Which, given the amount of effort and Claude tokens Yegge has sunk into building it, writing documentation, and publicly promoting it, Gas Town is not.

“Should developers still look at code?” will become one of the most divisive and heated debates over the coming years. You might be offended by the question, and find it absurd anyone is asking. But it’s a sincere question and the answer will change faster than you think.

I’m already seeing people divide along moralistic, personal identity lines as they try to answer it. Some declare themselves purist, AI skeptic, Real Developers who check every diff and hand-adjust specific lines, sneering at anyone reckless enough to let agents run free. While others lean into agentic maximalism, directing fleets from on high and pitying the mass of luddites still faffing about with manual edits like it’s 2019. Both camps mistake a contextual judgement for a personality trait and firm moral position.

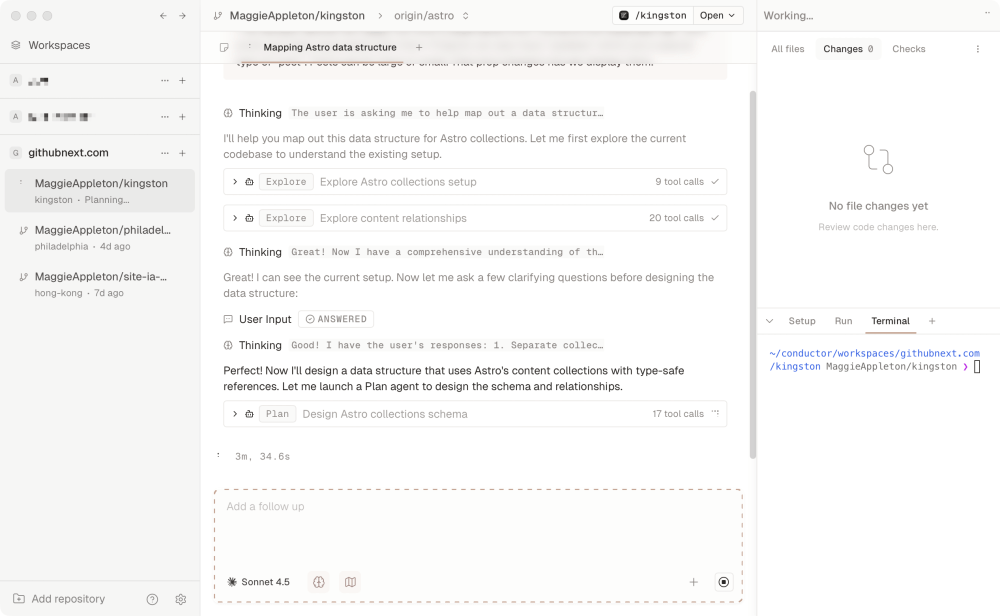

A more conservative, easier to consider, debate is: how close should the code be in agentic software development tools? How easy should it be to access? How often do we expect developers to edit it by hand?

Interfaces like Claude Code , Cursor , and Conductor do not put code front and centre in the experience. The agent is your first and primary interface. You might be able to see diffs rolls by or display code files inline, but you can’t touch them. Trying to edit code yourself is a roundabout journey of opening your IDE and navigating to the correct files and lines.

This design choice assumes it is easier to ask an agent to make the change for you, than it is to type it out the syntax yourself. They clearly say “we don’t believe users need to touch code.”

Framing this debate as an either/or – either you look at code or don’t, either you edit code by hand or you exclusively direct agents, either you’re the anti-AI-purist or the agentic-maxxer – is unhelpful. Because nothing is a strict binary.

The right distance isn’t about what kind of person you are or what you believe about AI capabilities in the current moment. How far away you step from the syntax shifts based on what you’re building, who you’re building with, and what happens when things go wrong. The degree of freedom you hand over to agents depends on:

Domain and programming language

Front-end versus backend makes a huge difference. Language is a poor medium for designing easing curves and describing aesthetic feelings – I always need to touch the CSS, and it’s often faster to just tweak directly than try to explain what I want. Yegge’s CLI tooling is much easier to validate with pass/fail tests than evaluating whether a notification system “feels calm enough”. Model competence also varies wildly by language; prompting React and Tailwind gives you much better results than Rust or Haskell, where the models still regularly choke on borrow checkers and type systems.

Access to feedback loops and definitions of succes

The more agents can validate their own work, the better the results. If you let agents run tests and see the output, they quickly learn what’s broken and how to fix it. If you let them open browsers, take screenshots, and click around, they can spot their mistakes. Tools like the Ralph Wiggum plugin lean into this – it loops until tests pass or some specific condition is validated. This doesn’t work for less defined, clear cut work though. If you try to make an agent design a visual diagram for you, it’s going to struggle. It doesn’t know your aesthetic preferences and can’t really “see” what it’s making.

Risk tolerance for shit going wrong

Stakes matter. If an agent breaks some images on your personal blog, you’ll recover. But if you’re running a healthcare system where a bug could miscalculate drug dosages, or a banking app moving actual money around, you can’t just wave an agent at it and hope. Consequences scale up fast. Corporate software has people whose entire job is compliance and regulatory sign-off – they need to see the code, understand it, verify it meets requirements. Those people aren’t going to let you widly run Gas Town over projects without serious guardrails in place.

“Gas Town sounds fun if you are accountable to nobody: not for code quality, design coherence or inferencing costs. The rest of us are accountable for at least the first two and even in corporate scenarios where there is a blank check for tokens, that can’t last. So the bottleneck is going to be how fast humans can review code and agree to take responsibility for it.”

Greenfield vs. brownfield projects

Starting fresh (greenfield), means you can let agents make architectural decisions and establish patterns – if you don’t like them, you can easily throw it out and restart. The cost of mistakes is low. But in an existing codebase (brownfield) with years of accumulated conventions, implicit patterns, and code that exists for reasons nobody remembers anymore, agents need much tighter supervision. They’ll happily introduce a new pattern that contradicts the three other ways this codebase already solves the same problem.

Number of collaborators

If you’re solo of course you can YOLO. If you’re working with more than a handful of people, you’ll have to agree on coding standards and agent rules. This creates its own overhead: updating the AGENTS.md file, picking MCPs, writing commands and skills and rules and whatever else we invent to constrain these things. The pace of change when you’re all using agents can be overwhelming and you need to figure out a sensible reviewing pipeline to manage it. Team coordination can fall apart when everyone’s agents start moving too fast. You might show up in the morning and discover someone’s agent renamed the database schema while another agent refactored the whole API layer, and neither of which jive with your giant, unmerged feature.

Your experience level

More senior developers can prompt better, debug better, and setup more stringent preferences earned through decades of seeing what can go wrong in scaled, production environments. They can recognize patterns: “oh, that’s a memory leak” or “that’s going to deadlock under load.” Newer developers don’t have that catalog of failures yet and are much more likely to prompt their own personal house of cards. The tests might pass and everything looks fine until you hit production traffic or someone enters a weird character. It is hard to defend against unknown unknowns.

Given all these “it depends” considerations, I’m currently in the code-must-be-close camp for most serious work done by professional developers. But I expect I’ll shift to the code-at-a-distance camp over the next year or two as the harnesses and tools we wrap around these agents mature. If we can ship them with essential safe guards and quality gates, the risks drop. Sure, the models will also improve, but the infrastructure matters far more: validation loops, tests, and specialised subagents who focus on security, debugging, and code quality are what will make code-at-a-distance feasible.

We have many, continuous versions of the code distance debate interally at Github Next . One of the projects within the team driving this is Agentic Workflows – autonomous agents run through GitHub Actions in response to events: new PRs, new issues, or specific times of day. Every commit can trigger a security review agent, an accessibility audit, and a documentation updater, all running in parallel alongside traditional CI/CD tests before anything lands in main. The team building it rarely touches code and do most of their work by directing agents from their phones. It’s these kinds of guardrails that makes a hands-off Sim-City-esque orchestrator system feel less terrifying to me.

I don’t believe Gas Town itself is “it”. It’s not going to evolve into the thing we all use, day in and day out, in 2027. As I said, it’s a provocative piece of speculative design, not a system many people will use in earnest. In the same way any poorly designed object or system gets abandoned, this manic creation is too poorly thought through to persist. But the problems it’s wrestling with and the patterns it has sketched out will unquestionably show up in the next generation of development tools.

As the pace of software development speeds up, we’ll feel the pressure intensify in other parts of the pipeline: thoughtful design, critical thinking, user research, planning and coordination within teams, deciding what to build, and whether it’s been built well. The most valuable tools in this new world won’t be the ones that generate the most code fastest. They’ll be the ones that help us think more clearly, plan more carefully, and keep the quality bar high while everything accelerates around us.