Kernel bugs hide for 2 years on average. Some hide for 20.

There are bugs in your kernel right now that won’t be found for years. I know because I analyzed 125,183 of them, every bug with a traceable Fixes: tag in the Linux kernel’s 20-year git history.

The average kernel bug lives 2.1 years before discovery. But some subsystems are far worse: CAN bus drivers average 4.2 years, SCTP networking 4.0 years. The longest-lived bug in my dataset, a buffer overflow in ethtool, sat in the kernel for 20.7 years. The one which I’ll dissect in detail is refcount leak in netfilter, and it lasted 19 years.

I built a tool that catches 92% of historical bugs in a held-out test set at commit time. Here’s what I learned.

| Key findings at a glance | |

|---|---|

| 125,183 | Bug-fix pairs with traceable Fixes: tags |

| 123,696 | Valid records after filtering (0 < lifetime < 27 years) |

| 2.1 years | Average time a bug hides before discovery |

| 20.7 years | Longest-lived bug (ethtool buffer overflow) |

| 0% → 69% | Bugs found within 1 year (2010 vs 2022) |

| 92.2% | Recall of VulnBERT on held-out 2024 test set |

| 1.2% | False positive rate (vs 48% for vanilla CodeBERT) |

The initial discovery

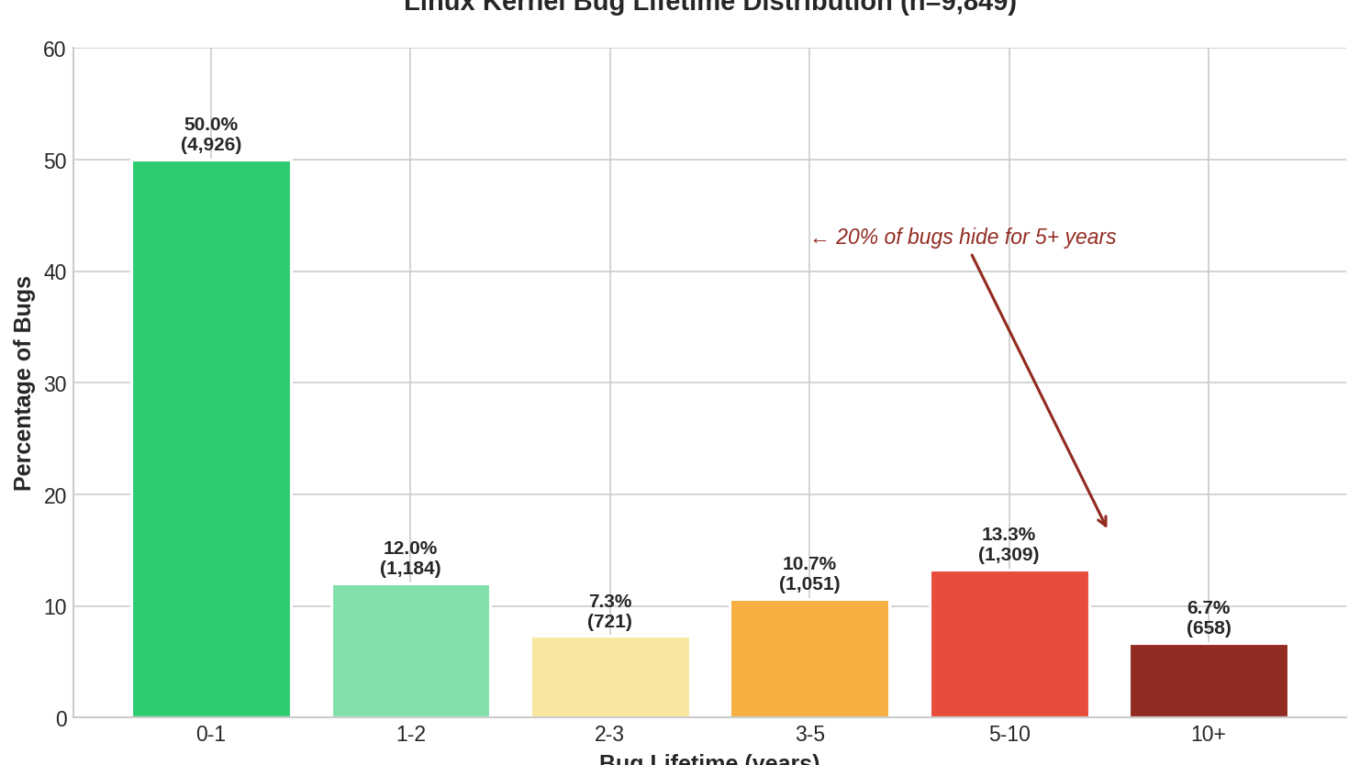

I started by mining the most recent 10,000 commits with Fixes: tags from the Linux kernel. After filtering out invalid references (commits that pointed to hashes outside the repo, malformed tags, or merge commits), I had 9,876 valid vulnerability records. For the lifetime analysis, I excluded 27 same-day fixes (bugs introduced and fixed within hours), leaving 9,849 bugs with meaningful lifetimes.

The results were striking:

| Metric | Value |

|---|---|

| Bugs analyzed | 9,876 |

| Average lifetime | 2.8 years |

| Median lifetime | 1.0 year |

| Maximum | 20.7 years |

Almost 20% of bugs had been hiding for 5+ years. The networking subsystem looked particularly bad at 5.1 years average. I found a refcount leak in netfilter that had been in the kernel for 19 years.

Initial findings: Half of bugs found within a year, but 20% hide for 5+ years.

But something nagged at me: my dataset only contained fixes from 2025. Was I seeing the full picture, or just the tip of the iceberg?

Going deeper: Mining the full history

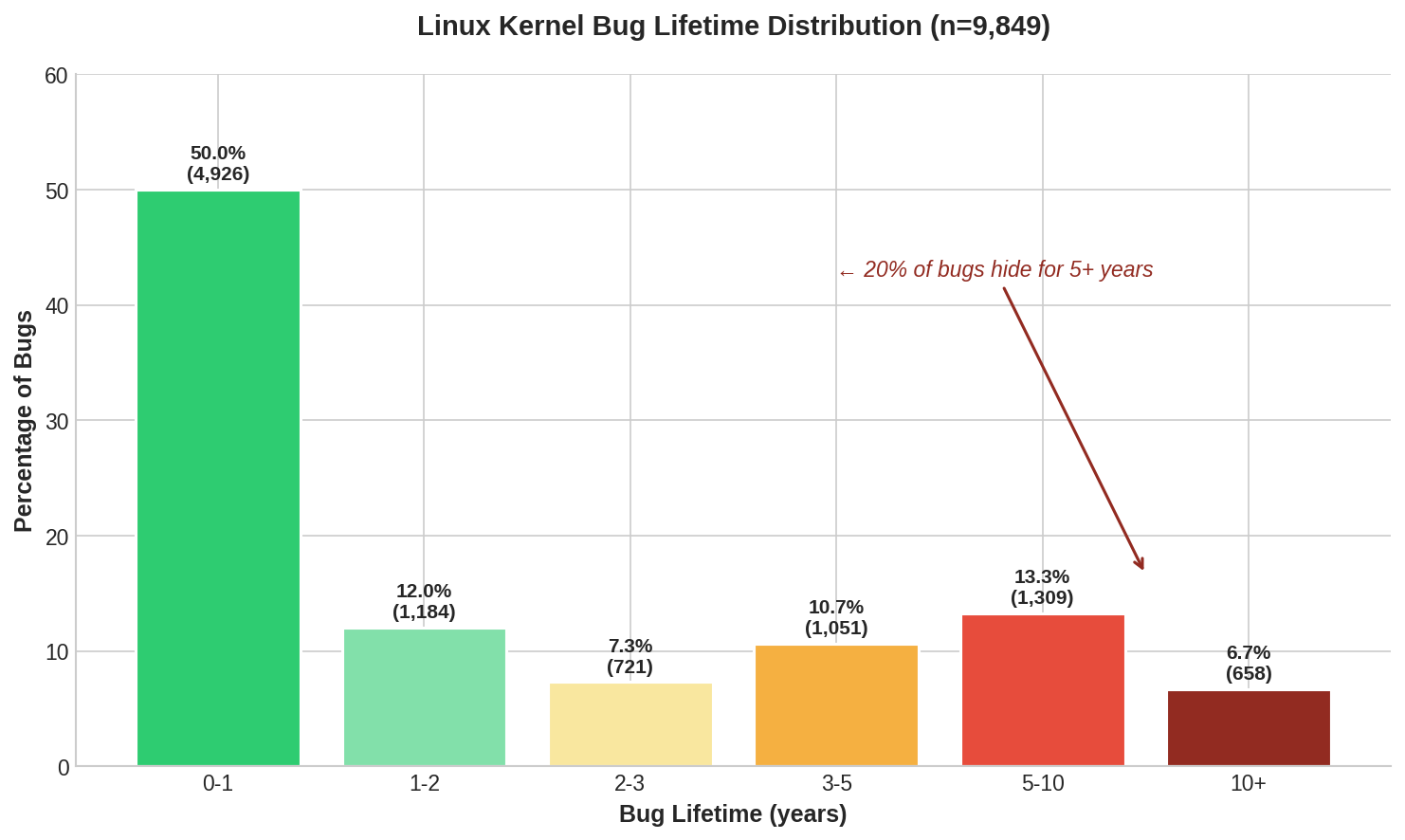

I rewrote my miner to capture every Fixes: tag since Linux moved to git in 2005. Six hours later, I had 125,183 vulnerability records which was 12x larger than my initial dataset.

The numbers changed significantly:

| Metric | 2025 Only | Full History (2005-2025) |

|---|---|---|

| Bugs analyzed | 9,876 | 125,183 |

| Average lifetime | 2.8 years | 2.1 years |

| Median lifetime | 1.0 year | 0.7 years |

| 5+ year bugs | 19.4% | 13.5% |

| 10+ year bugs | 6.6% | 4.2% |

Full history: 57% of bugs found within a year. The long tail is smaller than it first appeared.

Why the difference? My initial 2025-only dataset was biased. Fixes in 2025 include:

- New bugs introduced recently and caught quickly

- Ancient bugs that finally got discovered after years of hiding

The ancient bugs skewed the average upward. When you include the full history with all the bugs that were introduced AND fixed within the same year, the average drops from 2.8 to 2.1 years.

The real story: We’re getting faster (but it’s complicated)

The most striking finding from the full dataset: bugs introduced in recent years appear to get fixed much faster.

| Year Introduced | Bugs | Avg Lifetime | % Found <1yr |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 1,033 | 9.9 years | 0% |

| 2014 | 3,991 | 3.9 years | 31% |

| 2018 | 11,334 | 1.7 years | 54% |

| 2022 | 11,090 | 0.8 years | 69% |

Bugs introduced in 2010 took nearly 10 years to find and bugs introduced in 2024 are found in 5 months. At first glance it looks like a 20x improvement!

But here’s the catch: this data is right-censored. Bugs introduced in 2022 can’t have a 10-year lifetime yet since we’re only in 2026. We might find more 2022 bugs in 2030 that bring the average up.

The fairer comparison is “% found within 1 year” and that IS improving: from 0% (2010) to 69% (2022). That’s real progress, likely driven by:

- Syzkaller (released 2015)

- KASAN, KMSAN, KCSAN sanitizers

- Better static analysis

- More contributors reviewing code

But there’s a backlog. When I look at just the bugs fixed in 2024-2025:

- 60% were introduced in the last 2 years (new bugs, caught quickly)

- 18% were introduced 5-10 years ago

- 6.5% were introduced 10+ years ago

We’re simultaneously catching new bugs faster AND slowly working through ~5,400 ancient bugs that have been hiding for over 5 years.

The methodology

The kernel has a convention: when a commit fixes a bug, it includes a Fixes: tag pointing to the commit that introduced the bug.

commit de788b2e6227

Author: Florian Westphal <fw@strlen.de>

Date: Fri Aug 1 17:25:08 2025 +0200

netfilter: ctnetlink: fix refcount leak on table dump

Fixes: d205dc40798d ("netfilter: ctnetlink: ...")

I wrote a miner that:

- Runs

git log --grep="Fixes:"to find all fixing commits - Extracts the referenced commit hash from the

Fixes:tag - Pulls dates from both commits

- Classifies subsystem from file paths (70+ patterns)

- Detects bug type from commit message keywords

- Calculates the lifetime

fixes_pattern = r'Fixes:\s*([0-9a-f]{12,40})'

match = re.search(fixes_pattern, commit_message)

if match:

introducing_hash = match.group(1)

lifetime_days = (fixing_date - introducing_date).days

Dataset details:

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Kernel version | v6.19-rc3 |

| Mining date | January 6, 2026 |

| Fixes mined since | 2005-04-16 (git epoch) |

| Total records | 125,183 |

| Unique fixing commits | 119,449 |

| Unique bug-introducing authors | 9,159 |

| With CVE ID | 158 |

| With Cc: stable | 27,875 (22%) |

Coverage note: The kernel has ~448,000 commits mentioning “fix” in some form, but only ~124,000 (28%) use proper Fixes: tags. My dataset captures the well-documented bugs aka the ones where maintainers traced the root cause.

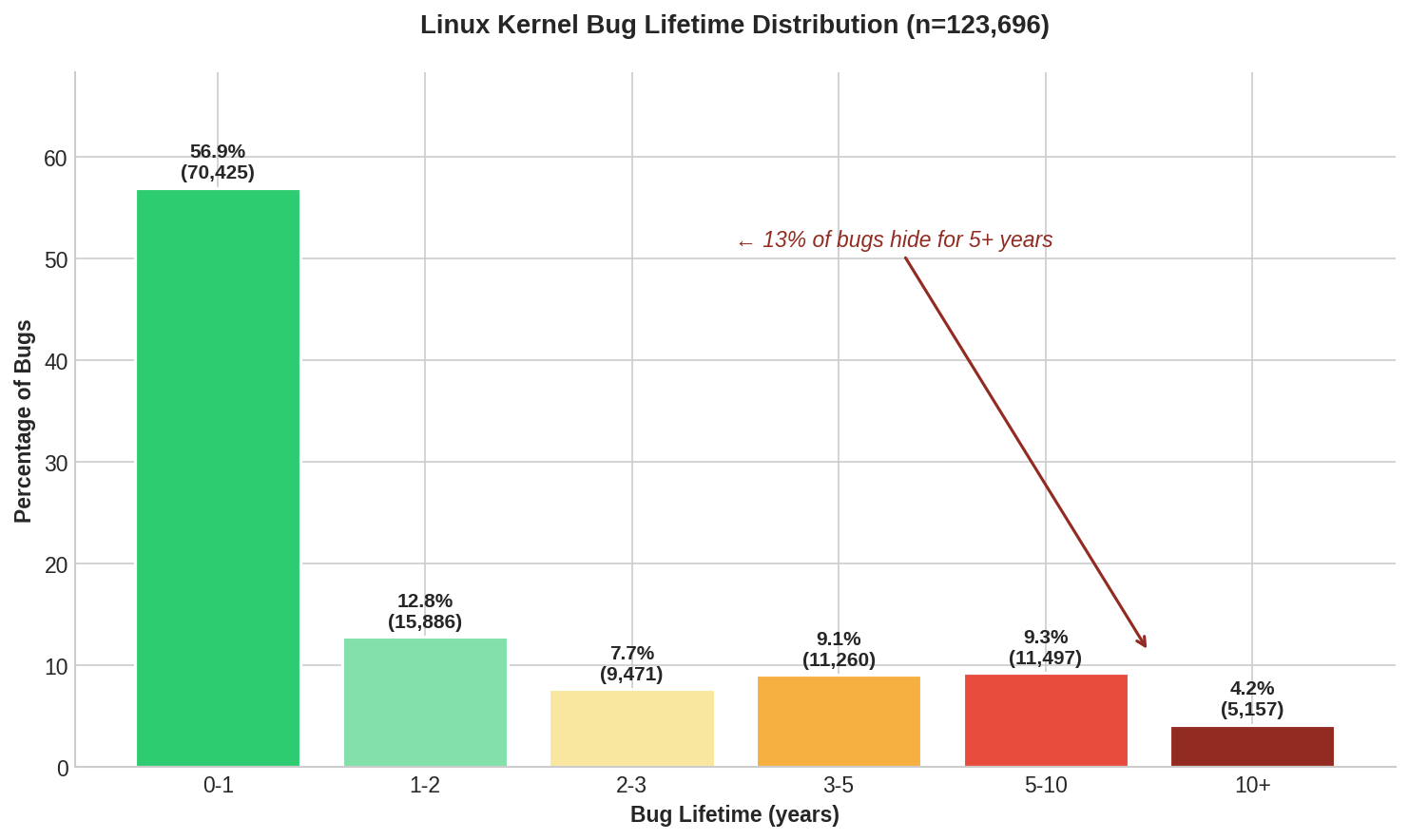

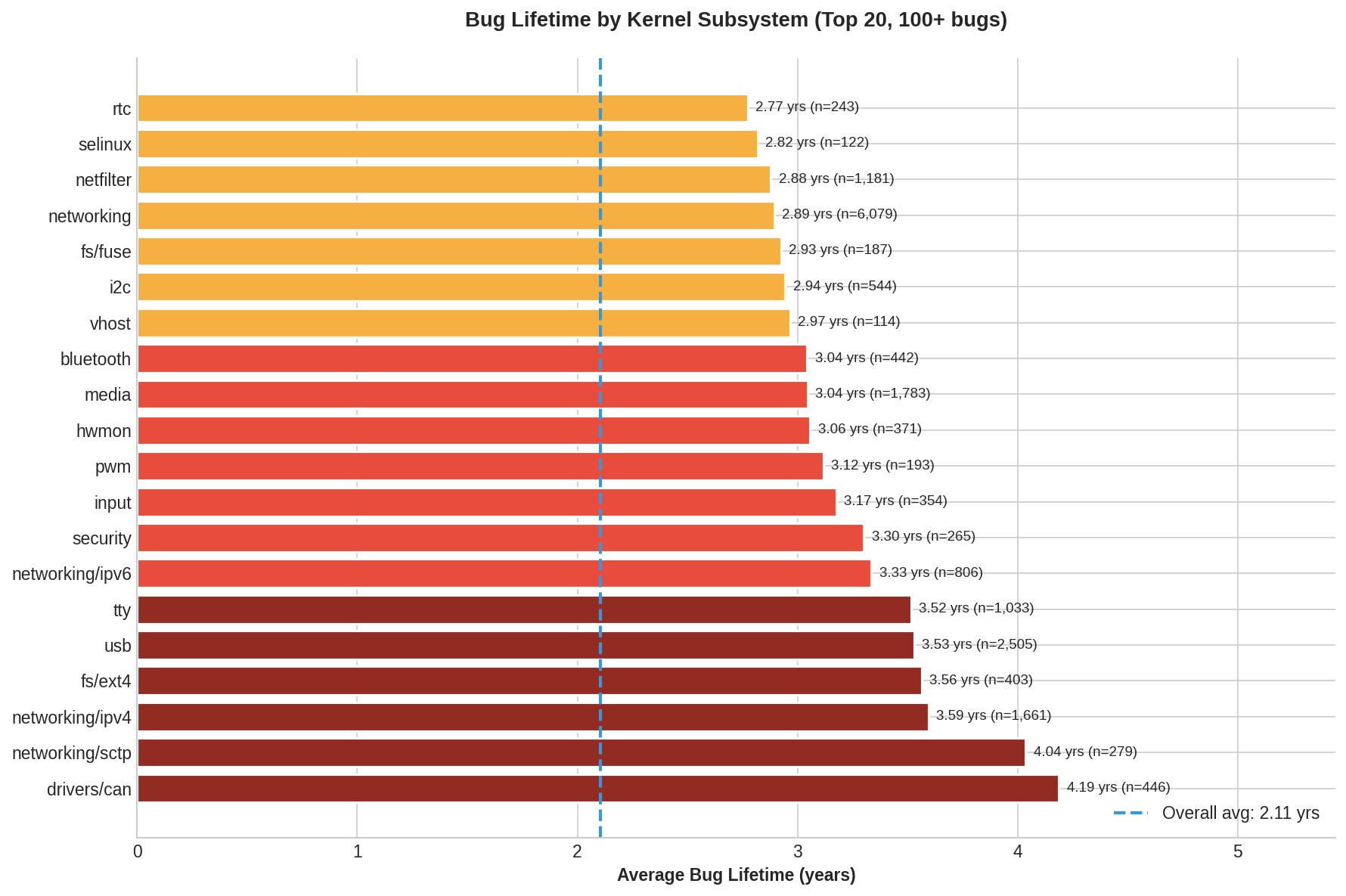

It varies by subsystem

Some subsystems have bugs that persist far longer than others:

| Subsystem | Bug Count | Avg Lifetime |

|---|---|---|

| drivers/can | 446 | 4.2 years |

| networking/sctp | 279 | 4.0 years |

| networking/ipv4 | 1,661 | 3.6 years |

| usb | 2,505 | 3.5 years |

| tty | 1,033 | 3.5 years |

| netfilter | 1,181 | 2.9 years |

| networking | 6,079 | 2.9 years |

| memory | 2,459 | 1.8 years |

| gpu | 5,212 | 1.4 years |

| bpf | 959 | 1.1 years |

CAN bus and SCTP bugs persist longest. BPF and GPU bugs get caught fastest.

CAN bus drivers and SCTP networking have bugs that persist longest probably because both are niche protocols with less testing coverage. GPU (especially Intel i915) and BPF bugs get caught fastest, probably thanks to dedicated fuzzing infrastructure.

Interesting finding from comparing 2025-only vs full history:

| Subsystem | 2025-only Avg | Full History Avg | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| networking | 5.2 years | 2.9 years | -2.3 years |

| filesystem | 3.8 years | 2.6 years | -1.2 years |

| drivers/net | 3.3 years | 2.2 years | -1.1 years |

| gpu | 1.4 years | 1.4 years | 0 years |

Networking looked terrible in the 2025-only data (5.2 years!) but is actually closer to average in the full history (2.9 years). The 2025 fixes were catching a backlog of ancient networking bugs. GPU looks the same either way, and those bugs get caught consistently fast.

Some bug types hide longer than others

Race conditions are the hardest to find, averaging 5.1 years to discovery:

| Bug Type | Count | Avg Lifetime | Median |

|---|---|---|---|

| race-condition | 1,188 | 5.1 years | 2.6 years |

| integer-overflow | 298 | 3.9 years | 2.2 years |

| use-after-free | 2,963 | 3.2 years | 1.4 years |

| memory-leak | 2,846 | 3.1 years | 1.4 years |

| buffer-overflow | 399 | 3.1 years | 1.5 years |

| refcount | 2,209 | 2.8 years | 1.3 years |

| null-deref | 4,931 | 2.2 years | 0.7 years |

| deadlock | 1,683 | 2.2 years | 0.8 years |

Why do race conditions hide so long? They’re non-deterministic and only trigger under specific timing conditions that might occur once per million executions. Even sanitizers like KCSAN can only flag races they observe.

30% of bugs are self-fixes where the same person who introduced the bug eventually fixed it. I guess code ownership matters.

Why some bugs hide longer

Less fuzzing coverage. Syzkaller excels at syscall fuzzing but struggles with stateful protocols. Fuzzing netfilter effectively requires generating valid packet sequences that traverse specific connection tracking states.

Harder to trigger. Many networking bugs require:

- Specific packet sequences

- Race conditions between concurrent flows

- Memory pressure during table operations

- Particular NUMA topologies

Older code with fewer eyes. Core networking infrastructure like nf_conntrack was written in the mid-2000s. It works, so nobody rewrites it. But “stable” means fewer developers actively reviewing.

Case study: 19 years in the kernel

One of the oldest networking bug in my dataset was introduced in August 2006 and fixed in August 2025:

// ctnetlink_dump_table() - the buggy code path

if (res < 0) {

nf_conntrack_get(&ct->ct_general); // increments refcount

cb->args[1] = (unsigned long)ct;

break;

}

The irony: Commit d205dc40798d was itself a fix: “[NETFILTER]: ctnetlink: fix deadlock in table dumping”. Patrick McHardy was fixing a deadlock by removing a _put() call. In doing so, he introduced a refcount leak that would persist for 19 years.

The bug: the code doesn’t check if ct == last. If the current entry is the same as the one we already saved, we’ve now incremented its refcount twice but will only decrement it once. The object never gets freed.

// What should have been checked:

if (res < 0) {

if (ct != last) // <-- this check was missing for 19 years

nf_conntrack_get(&ct->ct_general);

cb->args[1] = (unsigned long)ct;

break;

}

The consequence: Memory leaks accumulate. Eventually nf_conntrack_cleanup_net_list() waits forever for the refcount to hit zero. The netns teardown hangs. If you’re using containers, this blocks container cleanup indefinitely.

Why it took 19 years: You had to run conntrack_resize.sh in a loop for ~20 minutes under memory pressure. The fix commit says: “This can be reproduced by running conntrack_resize.sh selftest in a loop. It takes ~20 minutes for me on a preemptible kernel.” Nobody ran that specific test sequence for two decades.

Incomplete fixes are common

Here’s a pattern I keep seeing: someone notices undefined behavior, ships a fix, but the fix doesn’t fully close the hole.

Case study: netfilter set field validation

| Date | Commit | What happened |

|---|---|---|

| Jan 2020 | f3a2181e16f1 |

Stefano Brivio adds support for sets with multiple ranged fields. Introduces NFTA_SET_DESC_CONCAT for specifying field lengths. |

| Jan 2024 | 3ce67e3793f4 |

Pablo Neira notices the code doesn’t validate that field lengths sum to the key length. Ships a fix. Commit message: “I did not manage to crash nft_set_pipapo with mismatch fields and set key length so far, but this is UB which must be disallowed.” |

| Jan 2025 | 1b9335a8000f |

Security researcher finds a bypass. The 2024 fix was incomplete—there were still code paths that could mismatch. Real fix shipped. |

The 2024 fix was an acknowledgment that something was wrong, but Pablo couldn’t find a crash, so the fix was conservative. A year later, someone found the crash.

This pattern suggests a detection opportunity: commits that say things like “this is undefined behavior” or “I couldn’t trigger this but…” are flags. The author knows something is wrong but hasn’t fully characterized the bug. These deserve extra scrutiny.

The anatomy of a long-lived bug

Looking at the bugs that survive 10+ years, I see common patterns:

1. Reference counting errors

kref_get(&obj->ref);

// ... error path returns without kref_put()

These don’t crash immediately. They leak memory slowly. In a long-running system, you might not notice until months later when OOM killer starts firing.

2. Missing NULL checks after dereference

struct foo *f = get_foo();

f->bar = 1; // dereference happens first

if (!f) return -EINVAL; // check comes too late

The compiler might optimize away the NULL check since you already dereferenced. These survive because the pointer is rarely NULL in practice.

3. Integer overflow in size calculations

size_t total = n_elements * element_size; // can overflow

buf = kmalloc(total, GFP_KERNEL);

memcpy(buf, src, n_elements * element_size); // copies more than allocated

If n_elements comes from userspace, an attacker can cause allocation of a small buffer followed by a large copy.

4. Race conditions in state machines

spin_lock(&lock);

if (state == READY) {

spin_unlock(&lock);

// window here where another thread can change state

do_operation(); // assumes state is still READY

}

These require precise timing to hit. They might manifest as rare crashes that nobody can reproduce.

Can we catch these bugs automatically?

Every day a bug lives in the kernel is another day millions of devices are vulnerable. Android phones, servers, embedded systems, cloud infrastructure, all running kernel code with bugs that won’t be found for years.

I built VulnBERT, a model that predicts whether a commit introduces a vulnerability.

Model evolution:

| Model | Recall | FPR | F1 | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest | 76.8% | 15.9% | 0.80 | Hand-crafted features only |

| CodeBERT (fine-tuned) | 89.2% | 48.1% | 0.65 | High recall, unusable FPR |

| VulnBERT | 92.2% | 1.2% | 0.95 | Best of both approaches |

The problem with vanilla CodeBERT: I first tried fine-tuning CodeBERT directly. Results: 89% recall but 48% false positive rate (measured on the same test set). Unusable, flagging half of all commits.

Why so bad? CodeBERT learns shortcuts: “big diff = dangerous”, “lots of pointers = risky”. These correlations exist in training data but don’t generalize. The model pattern-matches on surface features, not actual bug patterns.

The VulnBERT approach: Combine neural pattern recognition with human domain expertise.

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ INPUT: Git Diff │

└───────────────────────────────┬─────────────────────────────────────┘

│

┌───────────────┴───────────────┐

▼ ▼

┌───────────────────────────┐ ┌───────────────────────────────────┐

│ Chunked Diff Encoder │ │ Handcrafted Feature Extractor │

│ (CodeBERT + Attention) │ │ (51 engineered features) │

└─────────────┬─────────────┘ └─────────────────┬─────────────────┘

│ [768-dim] │ [51-dim]

└───────────────┬───────────────────┘

▼

┌───────────────────────────────┐

│ Cross-Attention Fusion │

│ "When code looks like X, │

│ feature Y matters more" │

└───────────────┬───────────────┘

▼

┌───────────────────────────────┐

│ Risk Classifier │

└───────────────────────────────┘

Three innovations that drove performance:

1. Chunked encoding for long diffs. CodeBERT’s 512-token limit truncates most kernel diffs (often 2000+ tokens). I split into chunks, encode each, then use learned attention to aggregate:

# Learnable attention over chunks

chunk_attention = nn.Sequential(

nn.Linear(hidden_size, hidden_size // 4),

nn.Tanh(),

nn.Linear(hidden_size // 4, 1)

)

attention_weights = F.softmax(chunk_attention(chunk_embeddings), dim=1)

pooled = (attention_weights * chunk_embeddings).sum(dim=1)

The model learns which chunks matter aka the one with spin_lock without spin_unlock, not the boilerplate.

2. Feature fusion via cross-attention. Neural networks miss domain-specific patterns. I extract 51 handcrafted features using regex and AST-like analysis of the diff:

| Category | Features |

|---|---|

| Basic (4) | lines_added, lines_removed, files_changed, hunks_count |

| Memory (3) | has_kmalloc, has_kfree, has_alloc_no_free |

| Refcount (5) | has_get, has_put, get_count, put_count, unbalanced_refcount |

| Locking (5) | has_lock, has_unlock, lock_count, unlock_count, unbalanced_lock |

| Pointers (4) | has_deref, deref_count, has_null_check, has_deref_no_null_check |

| Error handling (6) | has_goto, goto_count, has_error_return, has_error_label, error_return_count, has_early_return |

| Semantic (13) | var_after_loop, iterator_modified_in_loop, list_iteration, list_del_in_loop, has_container_of, has_cast, cast_count, sizeof_type, sizeof_ptr, has_arithmetic, has_shift, has_copy, copy_count |

| Structural (11) | if_count, else_count, switch_count, case_count, loop_count, ternary_count, cyclomatic_complexity, max_nesting_depth, function_call_count, unique_functions_called, function_definitions |

The key bug-pattern features:

'unbalanced_refcount': 1, # kref_get without kref_put → leak

'unbalanced_lock': 1, # spin_lock without spin_unlock → deadlock

'has_deref_no_null_check': 0,# *ptr without if(!ptr) → null deref

'has_alloc_no_free': 0, # kmalloc without kfree → memory leak

Cross-attention learns conditional relationships. When CodeBERT sees locking patterns AND unbalanced_lock=1, that’s HIGH risk. Neither signal alone is sufficient, it’s the combination.

# Feature fusion via cross-attention

feature_embedding = feature_projection(handcrafted_features) # 51 → 768

attended, _ = cross_attention(

query=code_embedding, # What patterns does the code have?

key=feature_embedding, # What do the hand-crafted features say?

value=feature_embedding

)

fused = fusion_layer(torch.cat([code_embedding, attended], dim=-1))

3. Focal loss for hard examples. The training data is imbalanced where most commits are safe. Standard cross-entropy wastes gradient updates on easy examples. Focal loss:

Standard loss when p=0.95 (easy): 0.05

Focal loss when p=0.95: 0.000125 (400x smaller)

The model focuses on ambiguous commits: the hard 5% that matter.

Impact of each component (estimated from ablation experiments):

| Component | F1 Score |

|---|---|

| CodeBERT baseline | ~76% |

| + Focal loss | ~80% |

| + Feature fusion | ~88% |

| + Contrastive learning | ~91% |

| Full VulnBERT | 95.4% |

Note: Individual component impacts are approximate; interactions between components make precise attribution difficult.

The key insight: neither neural networks nor hand-crafted rules alone achieve the best results. The combination does.

Results on temporal validation (train ≤2023, test 2024):

| Metric | Target | Result |

|---|---|---|

| Recall | 90% | 92.2% ✓ |

| FPR | <10% | 1.2% ✓ |

| Precision | — | 98.7% |

| F1 | — | 95.4% |

| AUC | — | 98.4% |

What these metrics mean:

- Recall (92.2%): Of all actual bug-introducing commits, we catch 92.2%. Missing 7.8% of bugs.

- False Positive Rate (1.2%): Of all safe commits, we incorrectly flag 1.2%. Low FPR = fewer false alarms.

- Precision (98.7%): Of commits we flag as risky, 98.7% actually are. When we raise an alarm, we’re almost always right.

- F1 (95.4%): Harmonic mean of precision and recall. Single number summarizing overall performance.

- AUC (98.4%): Area under ROC curve. Measures ranking quality—how well the model separates bugs from safe commits across all thresholds.

The model correctly differentiates the same bug at different stages:

| Commit | Description | Risk |

|---|---|---|

acf44a2361b8 |

Fix for UAF in xe_vfio | 12.4% LOW ✓ |

1f5556ec8b9e |

Introduced the UAF | 83.8% HIGH ✓ |

What the model sees: The 19-year bug

When analyzing the bug-introducing commit d205dc40798d:

- if (ct == last) {

- nf_conntrack_put(&last->ct_general); // removed!

- }

+ if (ct == last) {

+ last = NULL;

continue;

}

if (ctnetlink_fill_info(...) < 0) {

nf_conntrack_get(&ct->ct_general); // still here

Extracted features:

| Feature | Value | Signal |

|---|---|---|

get_count |

1 | nf_conntrack_get() present |

put_count |

0 | nf_conntrack_put() was removed |

unbalanced_refcount |

1 | Mismatch detected |

has_lock |

1 | Uses read_lock_bh() |

list_iteration |

1 | Uses list_for_each_prev() |

Model prediction: 72% risk: HIGH

The unbalanced_refcount feature fires because _put() was removed but _get() remains. Classic refcount leak pattern.

Limitations

Dataset limitations:

- Only captures bugs with

Fixes:tags (~28% of fix commits). Selection bias: well-documented bugs tend to be more serious. - Mainline only, doesn’t include stable-branch-only fixes or vendor patches

- Subsystem classification is heuristic-based (regex on file paths)

- Bug type detection based on keyword matching in commit messages and many bugs are “unknown” type

- Lifetime calculation uses author dates, not commit dates, rebasing can skew timestamps

- Some “bugs” may be theoretical (comments like “fix possible race” without confirmed trigger)

Model limitations:

- 92.2% recall is on a held-out 2024 test set, not a guarantee for future bugs

- Can’t catch semantic bugs (logic errors with no syntactic signal)

- Cross-function blind spots (bug spans multiple files)

- Training data bias (learns patterns from bugs that were found, novel patterns may be missed)

- False positives on intentional patterns (init/cleanup in different commits)

- Tested only on Linux kernel code, may not generalize to other codebases

Statistical limitations:

- Survivorship bias in year-over-year comparisons (recent bugs can’t have long lifetimes yet)

- Correlation ≠ causation for subsystem/bug-type lifetime differences

What this means: VulnBERT is a triage tool, not a guarantee. It catches 92% of bugs with recognizable patterns. The remaining 8% and novel bug classes still need human review and fuzzing.

What’s next

92.2% recall with 1.2% FPR is production-ready. But there’s more to do:

- RL-based exploration: Instead of static pattern matching, train an agent to explore code paths and find bugs autonomously. The current model predicts risk; an RL agent could generate triggering inputs.

- Syzkaller integration: Use fuzzer coverage as a reward signal. If the model flags a commit and Syzkaller finds a crash in that code path, that’s strong positive signal.

- Subsystem-specific models: Networking bugs have different patterns than driver bugs. A model fine-tuned on netfilter might outperform the general model on netfilter commits.

The goal isn’t to replace human reviewers but to point them at the 10% of commits most likely to be problematic, so they can focus attention where it matters.

Reproducing this

The dataset extraction uses the kernel’s Fixes: tag convention. Here’s the core logic:

def extract_fixes_tag(commit_msg: str) -> Optional[str]:

"""Extract the commit ID from a Fixes: tag"""

pattern = r'Fixes:\s*([a-f0-9]{12,40})'

match = re.search(pattern, commit_msg, re.IGNORECASE)

return match.group(1) if match else None

# Mine all Fixes: tags from git history

git log --since="2005-04-16" --grep="Fixes:" --format="%H"

# For each fixing commit:

# - Extract introducing commit hash

# - Get dates from both commits

# - Calculate lifetime

# - Classify subsystem from file paths

Full miner code and dataset: github.com/quguanni/kernel-vuln-data

TL;DR

- 125,183 bugs analyzed from 20 years of Linux kernel git history (123,696 with valid lifetimes)

- Average bug lifetime: 2.1 years (2.8 years in 2025-only data due to survivorship bias in recent fixes)

- 0% → 69% of bugs found within 1 year (2010 vs 2022) (real improvement from better tooling)

- 13.5% of bugs hide for 5+ years (these are the dangerous ones)

- Race conditions hide longest (5.1 years average)

- VulnBERT catches 92.2% of bugs on held-out 2024 test set with only 1.2% FPR (98.4% AUC)

- Dataset: github.com/quguanni/kernel-vuln-data

If you’re working on kernel security, vulnerability detection, or ML for code analysis, I’d love to talk: jenny@pebblebed.com