A Union Pacific-Norfolk Southern combination would redraw the railroad map

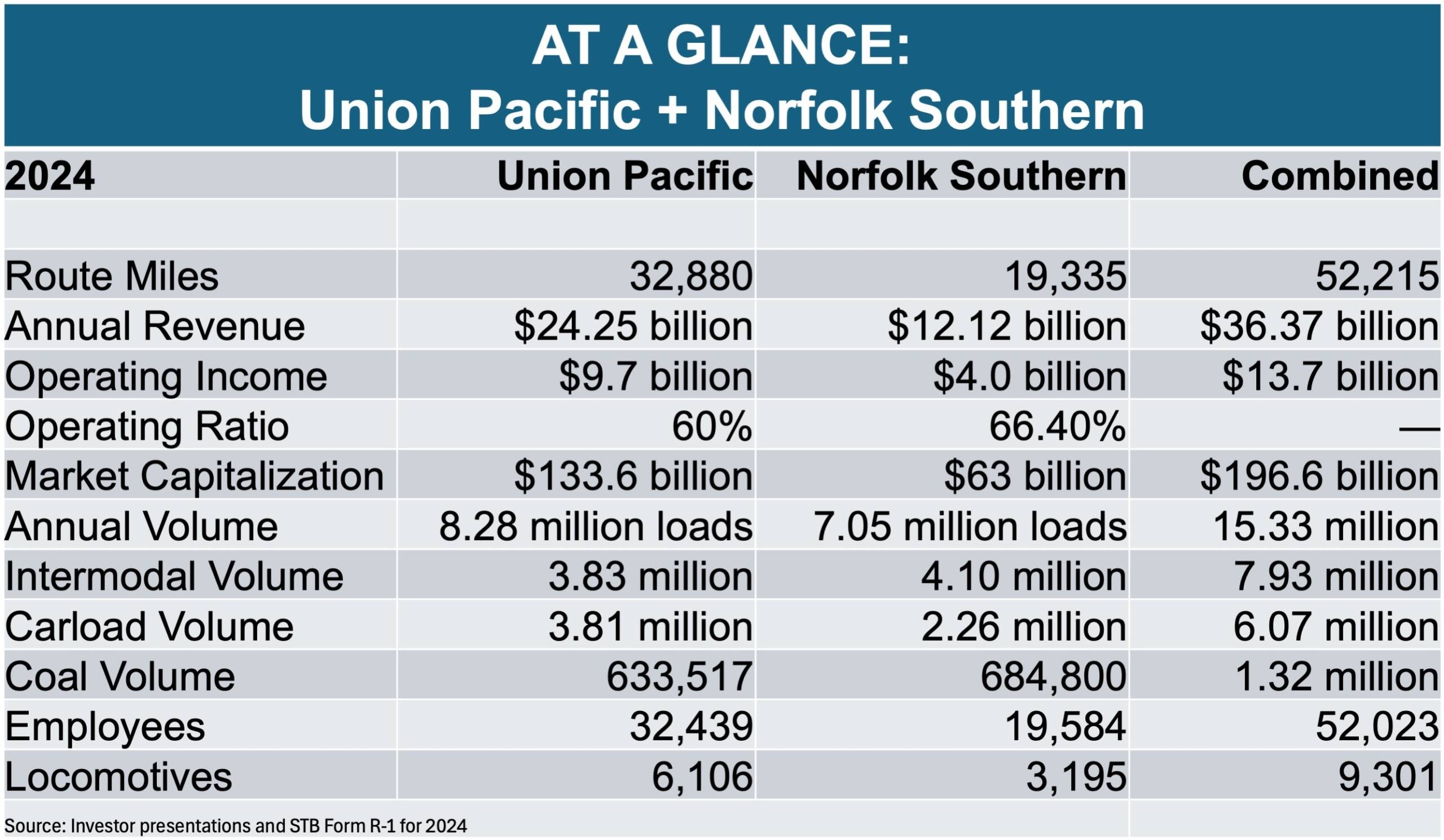

Combining Union Pacific and Norfolk Southern into the first transcontinental railroad in the U.S. would create a 52,215-mile colossus that could offer seamless service from coast to coast, bypassing longtime interchange choke points in Chicago and at gateways along the Mississippi River.

The two railroads confirmed today that they are in advanced merger discussions. The talks, they said, may not result in a deal. Plus, there’s the potential for a bidding war if BNSF Railway, UP’s Western rival, decides to make a move for NS. And there’s no guarantee that the first proposed merger involving two major Class I systems in more than 25 years would pass regulatory review in Washington.

But UP CEO Jim Vena, speaking on the railroad’s earnings call this morning, said the industry needs to move forward during a period of rapid technological change. “If you stand still, you get left behind,” he says.

A merger involving well-run railroads can boost the nation’s economy and help shippers because of the elimination of costly and time-consuming interchanges that can be unreliable, Vena says. “The more we can move off of highways onto our railroad, the more we allow our customers to be able to win in the marketplace,” he says.

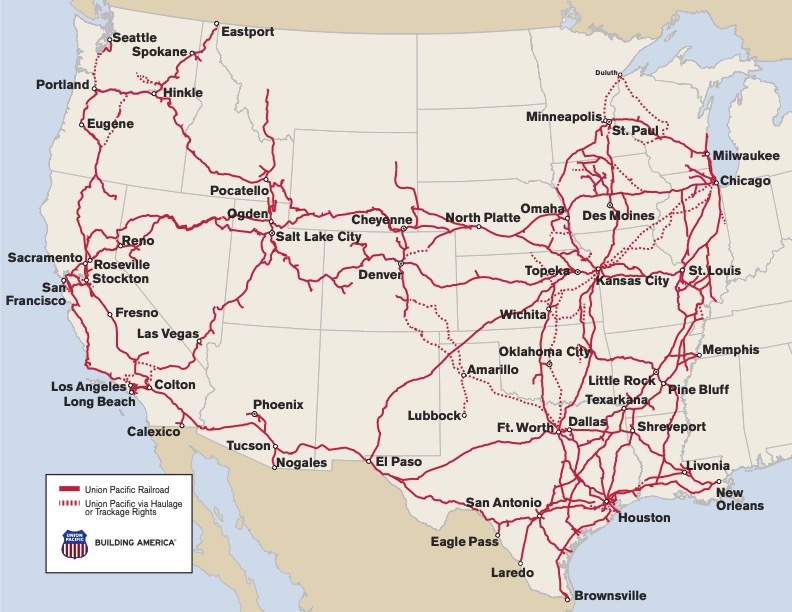

The railroad would stretch from Seattle, San Francisco, and Los Angeles to the Northeast, Mid-Atlantic, Atlanta, and Jacksonville, Fla., with lines blanketing the country’s midsection from the Twin Cities, Detroit, and Chicago to Dallas-Fort Worth, Houston, and the Mexican border.

Based on 2024 performance, the combined system would generate $36 billion in revenue, handle 15.3 million carloads and intermodal shipments, have 52,023 employees, and a locomotive roster of 9,301 units.

Analysts say a merger likely would lead to a loss of headquarters jobs but eventually would produce growth and more jobs for unionized workers.

UP and NS would bring different strengths to a combined system.

UP boasts the industry’s largest carload network, which is anchored by its crown jewel: Dominant access to Gulf Coast petrochemical plants and lucrative chemical traffic. Currently the lion’s share of this business bound for eastern destinations is exchanged with CSX, but a merger could shift traffic bound for Conrail Shared Assets areas in New Jersey and Philadelphia onto NS rails via Sidney, Ill., or Memphis.

Norfolk Southern operates the largest intermodal network in the East — including superior access to the distribution center network in eastern Pennsylvania, which is a huge intermodal destination that supplies retailers and their big box stores from the New York metro area to Washington.

But what would happen to J.B. Hunt, the largest intermodal company that partners with BNSF in the West and relies primarily on NS in the East? Industry observers say J.B. Hunt likely couldn’t have a foot in both camps and would have to depart for CSX, which would leave a big volume hole in NS territory.

A UP-NS merger also would put together strong automotive networks. NS originates more finished vehicle traffic than any other railroad, and UP is the No. 1 auto carrier in the West and reaches all major gateways with Mexico. With single-line service, they could avoid interchanges that currently rely on the Indiana Harbor Belt and Belt Railway of Chicago, as well as the Alton & Southern in St. Louis.

Some intermodal and carload growth could come from the so-called watershed area, which involves origins and destinations within a few hundred miles of the Mississippi River, the de facto dividing line between the Eastern and Western railroads. For two railroads, splitting a 500-mile move isn’t desirable because of difficulties and disagreements about dividing revenue. But a 500- to 750-mile haul would be attractive when it’s a one-railroad move.

The UP and NS bulk networks — which haul grain, coal, rock, and other unit train commodities like frac sand — likely would remain relatively unchanged by a merger, analysts say.

As an end-to-end merger, there is relatively little overlap between the UP and NS systems. Nearly all of it is in Missouri, where both railroads operate routes between Kansas City and St. Louis, and in Illinois.

One of those main lines — Norfolk Southern’s former Wabash from Detroit to St. Louis and Kansas City — would provide UP with a route from Kansas City to Chicago via Springfield, Ill., the connection with its former Gulf, Mobile & Ohio. Currently UP sends a pair of high-priority Z-symbol intermodal trains over BNSF trackage rights between K.C. and Chicago. The former Wabash-GM&O route would be slower, and the connection between UP and NS in Kansas City is over BNSF rails, however.

Current major UP-NS interchanges are located in Chicago, St. Louis, Kansas City, Memphis, Shreveport, La., and New Orleans.

The combined railroad likely would try to shift as much traffic out of Chicago and New Orleans as possible. Winners might be Kansas City, Memphis, and the Shreveport gateway — which links UP to NS via the CPKC-NS Meridian Speedway joint venture — and ties together the fast-growing Southwest and Southeast regions.

Independent analyst Anthony B. Hatch downplayed the impact of today’s announcement. “The only real news is that they are in advanced talks … but we knew last week they were in talks,” he says.

Hatch believes it’s likely that the railroads will reach a deal and file a merger application, and raised his odds of regulatory approval to 75%. But he said it’s unclear how UP and NS would satisfy the “enhanced competition” and “in the public interest” standards that are a part of the Surface Transportation Board’s untested 2001 merger review rules.

He also expressed concern about the downside risk of concessions or regulatory conditions that might be imposed on a merger, such as reciprocal switching that would give sole-served facilities access to a second railroad.

The STB’s 2001 rules also require merger applicants to address so-called downstream impacts of their combination, such as whether it would spark other mergers.

It is widely expected in industry circles that a first transcon would spark a second involving the remaining Western and Eastern carriers. BNSF and CSX representatives declined to comment today.

CSX CEO Joe Hinrichs, speaking on the railroad’s earnings call yesterday, said that the railroad was focused on its own efforts to improve service and gain volume. But he also said the railroad was interested in any opportunities that would reward shareholders and drive profitable growth.

BNSF has said that it does not see a catalyst for a transcontinental merger, since shippers, policymakers, and communities are not demanding one.