Trump administration guts CDC lab on sexually transmitted diseases

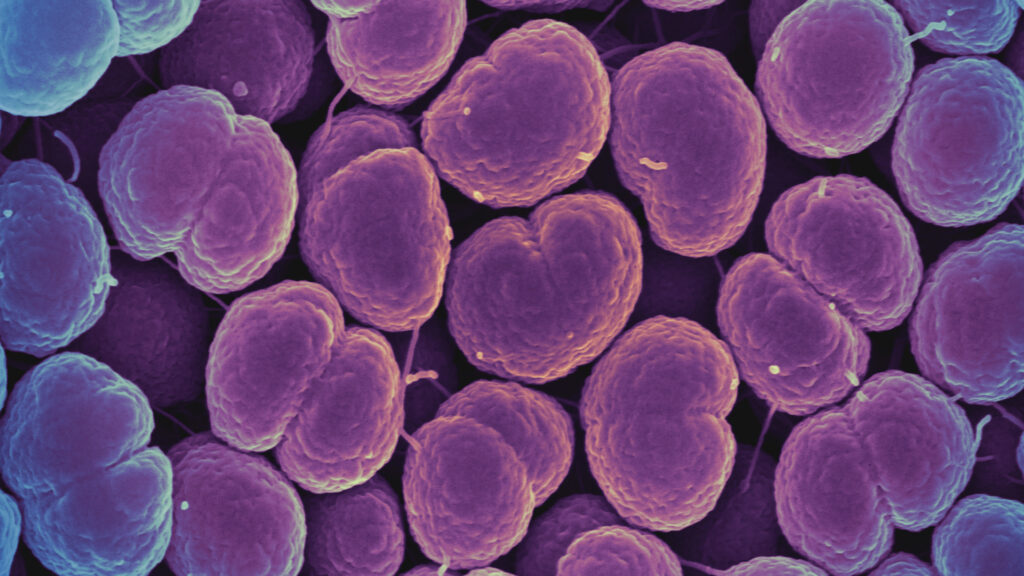

At a time when the world is down to a single drug that can reliably cure gonorrhea, the U.S. government has shuttered the country’s premier sexually transmitted diseases laboratory, leaving experts aghast and fearful about what lies ahead.

The STD lab at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention — a leading player in global efforts to monitor for drug resistance in the bacteria that cause these diseases — was among the targets of major staff slashing at the CDC this past week. All 28 full-time employees of the lab were fired.

STD clinicians and researchers were flummoxed, both because most of the other infectious diseases functions of the CDC were spared in this round of cuts, and because of the critical nature of the work the lab performed. Until the Trump administration announced the United States was withdrawing from the World Health Organization, the CDC lab was one of three international reference laboratories for STDs that worked with the WHO to conduct surveillance for infection rates and drug-resistance patterns and to recommend the best ways to treat these infections. The other two are in Australia and Sweden.

A CDC white paper on antibiotic resistance released during the first Trump administration listed drug-resistant gonorrhea as one of five urgent threats facing the country. Antimicrobial resistance to that last drug that reliably works to cure gonorrhea, ceftriaxone, is rare but on the rise globally.

“The loss of this lab is a huge deal to the American people,” said David C. Harvey, executive director of the National Coalition of STD Directors, which represents state, city, and U.S. territorial STD prevention programs across the country. “Without that lab, we would have not been able to appropriately diagnose and monitor drug-resistant gonorrhea.”

There has been no explanation from the Department of Health and Human Services, or its secretary, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., about why the STD lab was closed. When STAT asked the HHS press office about the closure, the response was swift — but wholly unrelated to the question posed.

“The critical work of the CDC will continue under Secretary Kennedy’s vision to streamline HHS to better serve the American people. The reorganization will strengthen the CDC with the transfer of the Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response (ASPR), responsible for national disaster and public health emergency response, to the agency, reinforcing its core mission to protect Americans from health threats,” Emily Hilliard, deputy press secretary, said via email.

A follow-up from STAT noting that the information provided was not about the STD lab drew no response.

Though STDs don’t garner as many headlines as Ebola, influenza, or Covid-19, they are among the most common diseases in the world — not just infectious diseases, but diseases period, said Jeffrey Klausner, a professor of medicine in infectious diseases, population, and public health at the USC Keck School of Medicine.

Klausner was shocked by the CDC lab’s closure. “To me, this is like a blind man with a chainsaw has just gone through the system and arbitrarily cut things without any rationale,” he said in an interview.

In terms of the decision’s implications for efforts to monitor for drug-resistant STDs, Klausner put it bluntly: “We are blind. As of [Tuesday], we are blind.”

Ina Park, a professor at the UCSF School of Medicine, and a co-author of the CDC’s 2024 laboratory guidelines for the diagnosis of syphilis, was also appalled.

“It’s just horrific and it’s so foolish and shortsighted,” Park said. “This administration has sometimes brought people back when they’ve realized that a service is vital and this is one of the times where I’m hoping that they will step up and do this.”

Klausner knows Kennedy personally, and reached out to tell him cutting the CDC’s STD lab was a mistake. As of Saturday, Klausner said he had not heard back from Kennedy on this issue.

The STD lab served multiple functions — updating treatment guidelines, monitoring resistance patterns, and working to develop better tests for syphilis, a resurgent infection for which existing tests are outdated.

It was a resource for clinicians who are having trouble curing patients of STIs that are not responding to treatment. Park noted she recently consulted on a case involving a woman who had been suffering for nine months from trichomoniasis, a vaginal infection. It was not responding to the treatments the woman’s physician prescribed. Park urged the treating doctor to send a sample to the CDC for additional testing, and the resulting treatment recommendation cured the infection.

The lab also leads the national surveillance for resistance patterns among STDs, generating genetic sequences of important isolates that it shares with the scientific community. That information is used in the development of tests and new therapeutics.

One of the fired employees, who asked not to be named for fear of reprisals, noted the lab holds the world’s largest repository of gonorrhea isolates — over 50,000, dating back to 1988 when the CDC began to collect them. Many of those isolates are in a freezer farm contracted by the CDC. What will happen to this invaluable scientific resource? It’s not clear.

“They’re irreplaceable. Even if you have new mutations now, you always need to track where they came from. The evolution, the pressures on what genes and all that. You need those older ones to really study that,” the individual said. “Are they just going to autoclave the whole thing and destroy it?”

The fired lab employee noted that the work that was being done at the CDC STD lab is not done elsewhere. “There’s no duplication. There is no lab like us at NIH” — the National Institutes of Health — “or at any university. The university [researchers], they rely on our specimens to do work. But if no one collects them, it’s just a real blow.”

Julie Dombrowski, a professor of medicine at the University of Washington and director of the Seattle and King County public health department’s HIV, STD and hepatitis C program, stressed that no one should expect the private sector to step in to fill the gap the closure has created.

“There is no commercial interest and little money to be made in this arena,” Dombrowski said in an email.

“It means we will lose ground in the fight against syphilis, we will be blind to national-level trends in antibiotic resistance among gonorrhea, and we will lose world-class expertise that will be very difficult to rebuild,” she said.

The loss of the CDC lab comes at a particularly fraught time.

Since the dawn of the antibiotic era, gonorrhea has systematically laid waste to every antibiotic used against it. The last reliably effective drug, ceftriaxone, is showing signs it too will soon be vanquished — reports of pan-resistant and extremely drug resistant gonorrhea have emerged in other parts of the world. What’s happening elsewhere will happen here, said Edward Hook, a professor emeritus at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, and an infectious diseases specialist who focuses on STIs.

“We live in a global village and these are global processes,” Hook said. “You can go from one side of the world to another in less than a day, and as a result the antibiotic resistance and public health threats can spread very, very quickly.”

For the first time in years, two new drugs for gonorrhea are nearing the end of the developmental pipeline — a major accomplishment. But given gonorrhea’s relentless development of resistance, it’s only a matter of time before it will develop the mutations needed to get around the new drugs too, said Barbara Van Der Pol, a professor of medicine and public health in the Heersink School of Medicine at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. Without the CDC lab, national efforts to monitor for resistance to the new drugs won’t exist, she said.

“So we’re going to have new drugs hit the market, but we’re not going to have a mechanism that has been vetted at the national level and is standardized that we can deploy quickly,” Van Der Pol said.

That lack of national standardization will create a situation where it’s hard to interpret what’s being seen, and when treatment guidelines ought to be changed, she said, likening the situation to the Wild West: “Everybody has a gun, but nobody knows when to use it.”

The loss of the lab also comes as clinicians are starting to adopt a new approach to trying to prevent sexually transmitted infections in people at high risk of acquiring them. As of last year, the CDC recommended that men who have sex with other men along with transgender women take a dose of the antibiotic doxycycline within 72 hours of having sex. The approach, known as doxy PEP — for post-exposure prophylaxis — has been shown to reduce syphilis and chlamydia infections by about 70% and gonorrhea infections by about 50%.

Although there is a lot of hope associated with this approach, there are also concerns it could drive antibiotic resistance. Implementing it in the absence of a laboratory tasked with monitoring drug resistance nationally strikes STD experts as imprudent. “We’ve lost one of our key tools to be able to monitor that resistance,” Klausner said. “This is a terrible time to be cutting off the ability to conduct surveillance,” Park said.

Have you been affected by cuts and restructuring at HHS?

*Required